I am a Polish Jew

15.02.2023

As soon as communism collapsed in Poland, he returned to the country because he also considered himself a Polish patriot. Arie then said: “We are all brothers and neither nationality nor religion can divide us. Why can't two nations, so bound together, cry over each other and enjoy freedom together?”

“He was a wonderful man, wise and cordial, of great knowledge and spirit” -- these were the words used to bid farewell to the Israeli politician and academic Shevah Weiss, the one-time ambassador of Israel to Poland, who died a week ago. Born in pre-war Poland and devoted to her for the last twenty years, Shevah Weiss will go down in history not just for the books he wrote and the students he inspired but also for his political initiatives and the beautiful friendships he forged. For many commentators in Poland, a simple sentence that Shevah Weiss uttered more than two decades ago in Jedwabne on July 10, 2001 and which he was to repeat on numerous subsequent occasions, sums up why he will be remembered forever. In that singular remark, he refers to two barns, explaining that there were many different barns in occupied Poland -- not just the one in Jedwabne, but, for example, the one in Borysław too -- where Jews were rescued. And why? Because little Shevah, his brother and parents were saved from the Holocaust thanks to their neighbors, Polish and Ukrainian families.

This extraordinary man was also able to say that it was not just Jews, but Poles too, who were the victims of Nazism and Hitlerism. He knew history and while capable of pointing out the shortcomings and awkwardness in the two countries’ mutual relations in recent decades, he was also quick to cite positive examples within the context of those relations including Polish patriots with Jewish roots. Everyone acknowledges how exceptional he was. Yet, despite the fact that some might prefer to see him as the only one having such a deeply human approach to Jewish and Polish matters, Shevah was not alone.

He kept finding good things

It was during his term as ambassador, albeit without his participation, that Ruven Zygielbaum (1913–2005), the youngest brother of Artur Szmul Zygielbojm, the great lonely hero of the struggle to draw the Allied world’s attention to the fate of Jews dying in occupied Poland, re-emerged .

Ruven, an actor, was found living in South Africa by the then Polish ambassador Krzysztof Śliwiński, who in Ruven’s own words, “returned him to Poland”, initially to the tiny territory encompassed by the Polish embassy in Pretoria, and later, at the invitation of Prime Minister Jerzy Buzek, to the country on the Vistula River. Following his first trip in 2000, he was to return regularly for six months every year. Then, in 2004, he decided to return permanently. He kept on discovering and falling in love with this new Poland. He never said much about what he didn't like, always finding something positive and good. This was especially true when he spoke to the young people he met in parish halls and schools about his brother -- Artur Szmul Zygielbojm.

In 2000, Ruven, the youngest of the eleven Zygielbojm siblings, had already appeared in the excellent documentary "The Death of Zygielbojm" ("Śmierć Zygielbojm", directed by Dżamila Ankiewicz, 1961-2016) where he talked to people like Lidia Ciołkoszowa, Jan Karski, Felek Scharf and Marek Edelman who had known his brother.

During these meetings with the youth, Ruven was no longer just an actor after any audience. His talks in places like Otwock, Krasnystaw, Warsaw, Bodzanów, Laski and Wrocław carried a message of dialogue and reconciliation. He was always able to establish good rapport with his young audiences, sustaining their interest in his stories, himself as part of his message. He firmly believed that these young people, and himself among them, constituted the kind of Poland his brother Artur had dreamed of and talked about.

Ruven’s last meeting with students took place in the large parish hall of St. James Church on Narutowicz Square in Warsaw, on January 16, 2005. In a dozen or so days, Ruven was to turn 92, so they presented him with roses and their birthday wishes. What pleased him most, however, was a statement by Father Grzegorz Michalczyk that the meeting marked the beginning of the Day of Judaism celebration. He was proud of it and full of joy – just as he had been during his stays in Laski, where he would stay with the Franciscan sisters, telling other guests that while he was not a clergyman, he was definitely a spiritual one.

"I am not a Jew from Poland," he would also add. "I am a Polish Jew."

He gave us friendship and trust. On Christmas Eve 2004, he joked with satisfaction that "at this age" you can do something for the first time. There were eighteen of us at the table, including a Polish family with two daughters, who had just arrived in our country from Ukraine. The multitude of guests delighted Ruven, because it reminded him the family celebrations during his childhood in Krasnystaw.

He wanted to be buried in Poland.

The door has been opened

Another friend of our family, Arie Lerner (1918–2002) had the same desire. He was a man of inexhaustible energy with an equally indefatigable faith in positive action, which he undertook constantly with new ideas to bridge the divisions and bring the two nations closer together.

Part of Hitler's racist myth was his rejection of the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, the God of Jesus Christ, Benedict XVI said.

see more

In 1992, I was a co-organizer of a unique, and to this day never repeated, march that combined two monuments and two uprisings: the Monument to the Warsaw Uprising and the Monument to the Ghetto Heroes. Arie Lerner was the creator and, one could say, God's madman, who inspired us, a small group, to act and ignited in us faith in its success and a deeper sense.

I wrote about him in "Tygodnik Solidarność" and "Idziemy" [Polish weeklies]. He survived the war in a coal mine in the Urals. After returning, he was a vice-consul in the Israeli embassy and as a result ended up in a Stalinist prison. There, although tortured, he did not give up and did not allow himself to be "framed" into the alleged world Zionist conspiracy. Released after a few years, he left for Israel, where he was building houses and the Yad Vashem Institute, and met up with his persecutors from Rakowiecka – an experience that gave rise to bitter feelings when he attempted to seek justice. Once communism fell in Poland, he returned to Poland, because he also considered himself a Polish patriot. Arie said: “We are all brothers and neither nationality nor religion can divide us. Why can't two nations, so bound together, cry over each other and enjoy freedom together?

Few people wanted to get involved in "his" march, during which the presence and prayers of Polish and Israeli youth brought together the victims of the war and destruction created by the Germans and Soviets. But Arie was not one to easily give up. He assembled an honorary committee, including such personalities as the Israeli writer Miriam Akavia, professor Andrzej Stelmachowski, the resistance fighter Stanisław Jankowski "Agaton" and the Israeli ambassador Miron Gordon. Everything worked out, including participation by the army. But the march was never repeated. It was never possible to honor the heroes of both Warsaw Uprisings or the victims of both cataclysms in one march again. Yes, a year later, the Polish Council of Christians and Jews initiated the March of Prayer along the route of the Monuments of the Warsaw Ghetto, and yes, there is the Prayer at the Stone of the Righteous but we still can't follow the message of Ari Lerner and honor all the victims of that time together.

"But the door has been opened," he used to say, "and a door once opened cannot be closed."

The same God is everywhere

The door was also opened by Henryk Prajs (1916-2018), called by cavalry enthusiasts "the last light horseman of the Second Polish Republic". Until the end of his long life, Mr Prajs talked about his service in the army, about how much it had given him, the pride with which he wore a cap with a yellow rim in the colors of the 3rd Light Cavalry Regiment in Suwałki named after Col. Jan Hipolit Kozietulski, the joy he experienced when he went on leave in his town Góra Kalwaria, where everyone could see him in his uniform. Years later, he would describe how he, the skinny Abramek, had grown manly and serious.

He was a soldier in September, 1939, wounded in the battle of Olszew in Podlasie, and as long as he had strength, he went there for the celebration of this anniversary. He became a friend with students and teachers of the local school. He remembered the names of his platoon mates and the names of the horses until the end of his life. He spoke only good things about Poland, with love and respect. And that is why he so strongly and generously supported the youth who formed the voluntary cavalry, put on uniforms, learned to ride a horse and wield a saber and a lance. He believed these young people also loved Poland. He celebrated his 100th birthday both in the synagogue as well as in the church. “Wherever I go, I pray,” he used to say. “God is the same everywhere.”

He never forgot about his loved ones murdered in the Holocaust. He talked about them during meetings with young people, but also about his neighbors who had saved him.

All three protagonists of my story rest today in the same soil, at the Jewish Cemetery in Warsaw, at Okopowa Street.

Joanna Brańska, a friend of mine who died prematurely and whose enormous contribution to Polish-Jewish rapprochement has not yet been described or evaluated, would add many more names to this list. I will mention only three. The first one is the singer Towa Ben Cewi (born in 1928) from Łódź. She was the only survivor of the large family of a cantor. After the war, she settled in Israel. There as well as after the fall of communism in Poland, she taught young people that "the whole world is one big bridge, and what is important, what is really important is not to be afraid, not to be afraid at all".

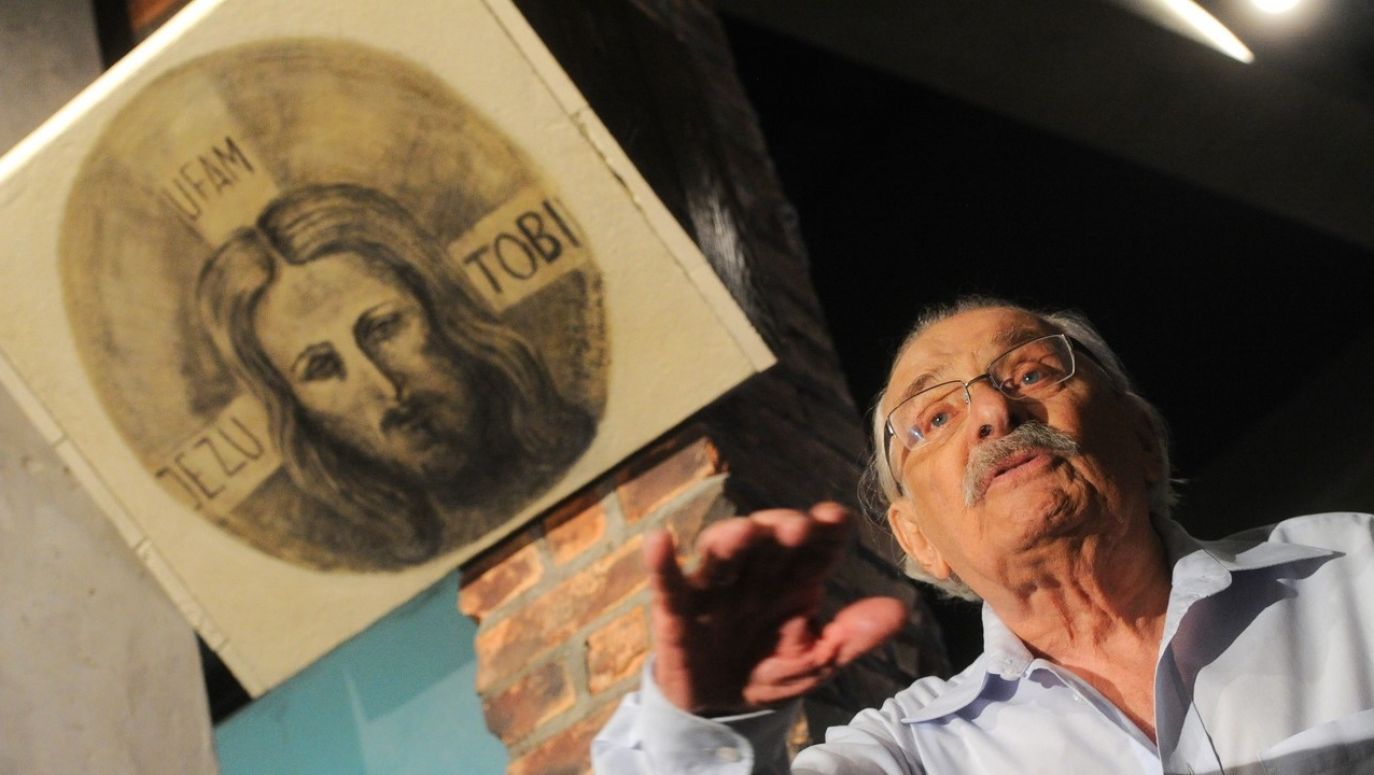

The second name belongs to Samuel Willenberg (1923–2016), famous for his rebellion and escape from the Treblinka Death Camp. Later he became a soldier in the Warsaw Uprising. He was connected with Poland until the end of his long life. He would come here with Israeli youth and taught them not only about the Holocaust, but also about Poland. After retirement, when he no longer worked as a surveying engineer, he became a sculptor and designed the Monument to the Victims of the Częstochowa Ghetto, unveiled in 2009. During the Warsaw Uprising, his father, the artist Perec Willenberg, drew the face of Christ with the inscription "Jesus, I trust you" on the wall of the staircase in the tenement house at 60 Marszałkowska Street. The drawing was immediately surrounded by worshippers.