Michel Houellebecq returns with his eighth novel. In

anéantir [lit. “Destroy”] the author transports the reader to the reality of the 2027 presidential campaign, in order to touch upon themes of old age, death, euthanasia or the decline of the West in the atmosphere of a pessimistic political-metaphysical thriller. Through the ajar gates of Schopenhauerian pessimism, however, a spark of hope shines through.

Like every other book by this author, this one too has generated a considerable response in France, both in the traditional and social media. In the latter, the number of relevant hashtags testifies to the popularity among readers, the presence of the subject in the press, radio and television is more a testimony to the controversy surrounding the author, his position and achievements – disputes often of a political nature.

A white bourgeois’s last will?

For it must be remembered that in France, literature is a highly politicised domain. In fact, it is not so much literature itself as literary criticism which extends the domain of struggle, eagerly dividing authors according to political criteria and labelling them as “left-” or “right-wing” whenever it finds the slightest pretext for doing so – not only in their views or in the works themselves, but also in their critical reception.

There are, indeed, writers who are objectively far-right, such as Laurent Obertone and his post-apocalyptic

Guerilla about the civil war in France, or far-left, such as Didier Daeninckx, whose novels are anti-fascist denunciations, but in most cases it is literary criticism that provides labels

comme il faut.

In the case of Houellebecq’s new novel, it is no different. It was positively received in the centre-right

Le Figaro, the right-wing

Valeurs actuelles found the subject worthy of a cover story, while for the left-wing

Marianne anéantir immediately became the whipping boy. Left-wing media reviewers exerted their cruelty over the novel by outdoing each other in inventing colourful formulas: “a testament to a white bourgeois detached from reality”, “a dream of a reactionary world where men have power over women and immigrants keep their heads down”, “the author bashes women, blacks, the working class, journalists”, “it’s not a far-right novel, it’s a novel that trivialises the far right”, etc.

And everyone was outdone by the website Médiapart, writing that

anéantir is “a handbook for misogynistic old white men who can no longer get ‘it’ up”.

The marketing plan

Houellebecq made readers wait two years after his previous novel

Serotonin. The new book was published in France on 7 January 2022, one day seven years after the bloody attack on “Charlie Hebdo”. Could it be that the publisher chose this date on purpose? The release of one of the writer’s previous novels,

Submission, which deals with the Islamisation of France, coincided with this Islamist attack in 2015. It is known that Houellebecq, in deep shock at the time, abandoned the promotional tour and left Paris, having no desire to step into the shoes of a prophet whose darkest visions had unwittingly come true.

The promotional campaign for

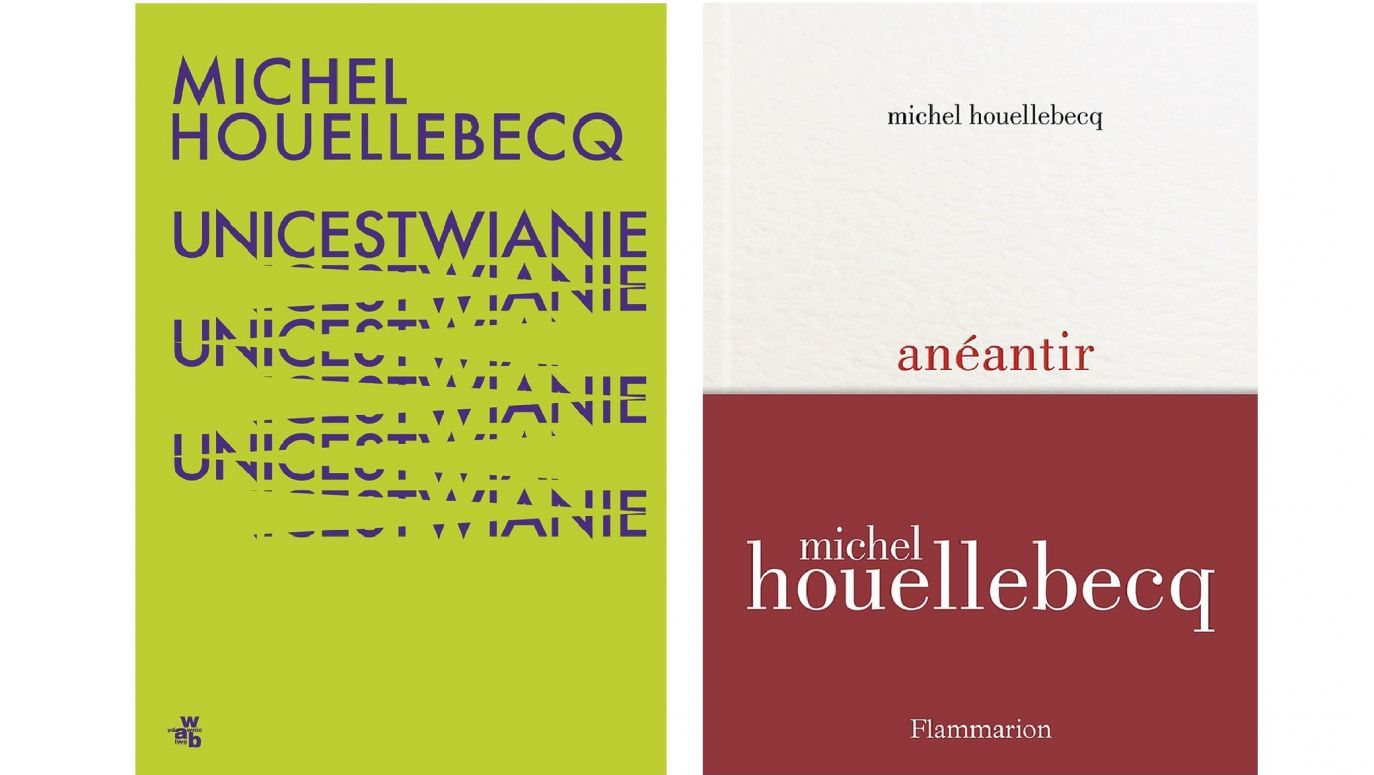

anéantir was meticulously planned according to a marketing plan. The publisher, Flammarion, carefully released small leaks to the press, as if from a drip, revealing bit by bit the volume of the first print run or the title, which was only revealed on 17 December.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

The 600 journalists and critics who got their hands on the text of the novel were embargoed from revealing the contents until 30 December. The only thing missing was a bunker for the translators and we would almost have had the case of the last volume of the “Harry Potter” series.

The author himself actively participated in this project by giving his opinion on the paperweight, choosing the colour of the cover, supposedly inspired by The Beatles’ white album, and requesting that the title of the novel – “anéantir” meaning “to annihilate” – be written in lowercase.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE