The Holy See has perhaps 180 such agreements, including with international organisations and with countries that are not Catholic at all.

see more

Moreover, the principles of the congregation’s organizational and spiritual work were developed in such a way that it operates to this day and runs schools, kindergartens, and nursing homes – in 145 religious houses in Poland, Brazil, Italy, Belarus, Ukraine and Russia. It survived despite many years of trouble with approving legal acts, prohibitions of activity, wars. It developed constantly, and during World War II it dealt with saving Jewish children under the leadership of the fearless mother Matilda Getter

which we showed on our website).

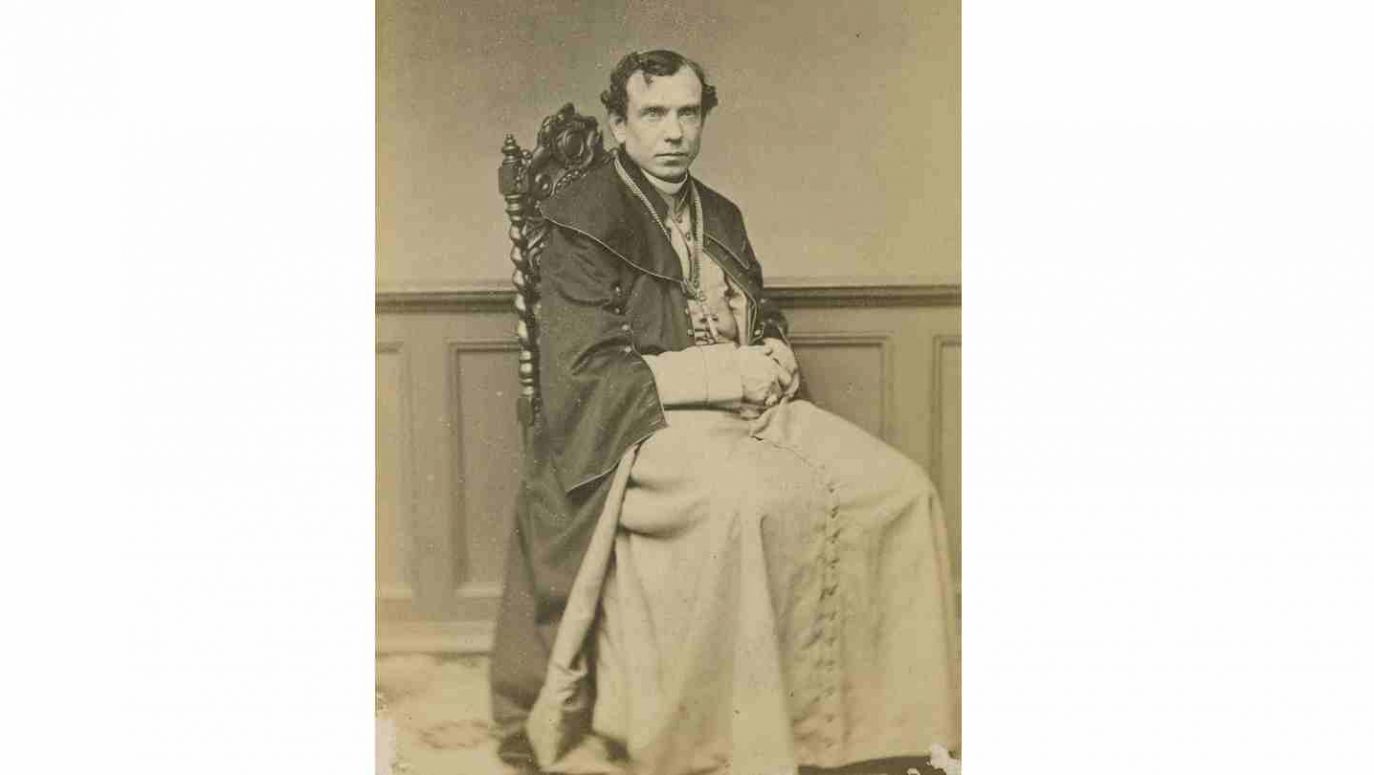

The relatively young priest Feliński became famous in St. Petersburg as an outstanding preacher and charismatic – as we would say today – priest, also a confessor and spiritual guide. Several Russian aristocrats converted to Catholicism under his influence, Aneta Malcow joined the Congregation of the Sisters of the Family of Mary, and the imperial adjutant, Baron Leo Pavlovich Nikolai, joined the Carthusians and left for Grenoble.

Father Feliński, as a professor of the Spiritual Academy, did not limit himself to lectures and examinations. “Contrary to a large part of the clergy of the time, fearful of secular authority and often servile, he represented a new type of priest: educated, well-versed in his rights and duties, obedient to the ecclesiastical authority, loyal to the secular authority, without betrayal and secret plots, but boldly expressing his convictions and able to resist pressure from the government directed against the Church” – writes sister Antonietta Frącek, PhD from this congregation, an outstanding archivist and tireless researcher of the life of the holy founder.

Opinions reached the Vatican that “the good and the bad consider him the best priest in Russia”.

So when on January 6, 1862, the news spread that the Pope was appointing Father Zygmunt Szczęsny Feliński as Archbishop of Warsaw, regret arose in the Catholic circles of St. Petersburg. All the more so because Pope Pius IX, kind to Poles, made this appointment in a great hurry, “because of the unfortunate situation of the country”.

During the meeting with Tsar Alexander II, the new archbishop did not hide that “if the Nation did not take into account my representations and drew upon itself the dangerous consequences of repression, I would first of all fulfill my duties as a Shepherd and share the misfortune of my people, even if it became the perpetrator of its misfortunes itself”.

They saw a tsarist agent in him

The situation in Warsaw was already very tense: for several months there had been martial law, curfew, arrests, imprisonment and deportation of lay people and clergy to Siberia.

Churches had been closed for four months by church authorities in protest against the bloody repression of February 27, 1861.

On that day, Warsaw students organized a demonstration. Its participants demanded, among others, the release of those arrested during the earlier demonstration on February 25, 1861. The Russian army opened fire on the protesters in Krakowskie Przedmieście. Five people were shot and killed. During the riots, the police and the Russian army stormed the churches where the demonstrators were hiding. So they were soon closed in protest. As a sign of solidarity with Catholics, Rabbi Izaak Kramshtyk ordered all Warsaw synagogues to be closed too.

On April 8, at Castle Square, the tsarist army pacified another demonstration, and its symbol was Michał Landy, a rabbinical school student, who died with a cross picked up from the hands of a casualty.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

Agata Kłosek, PhD, from the University of Warsaw said during a conference devoted to him in June this year that although Archbishop Feliński began to create literary texts only during his exile, in Russia, at the age of over 40, they stand the test of time. In addition to excellent sermons, he wrote very interesting and literary diaries, philosophical essays on social issues, and poems.

Agata Kłosek, PhD, from the University of Warsaw said during a conference devoted to him in June this year that although Archbishop Feliński began to create literary texts only during his exile, in Russia, at the age of over 40, they stand the test of time. In addition to excellent sermons, he wrote very interesting and literary diaries, philosophical essays on social issues, and poems.