Do we want to commune with horrific images of bent train carriages and bleeding bodies or animals deprived of any chance of survival?

see more

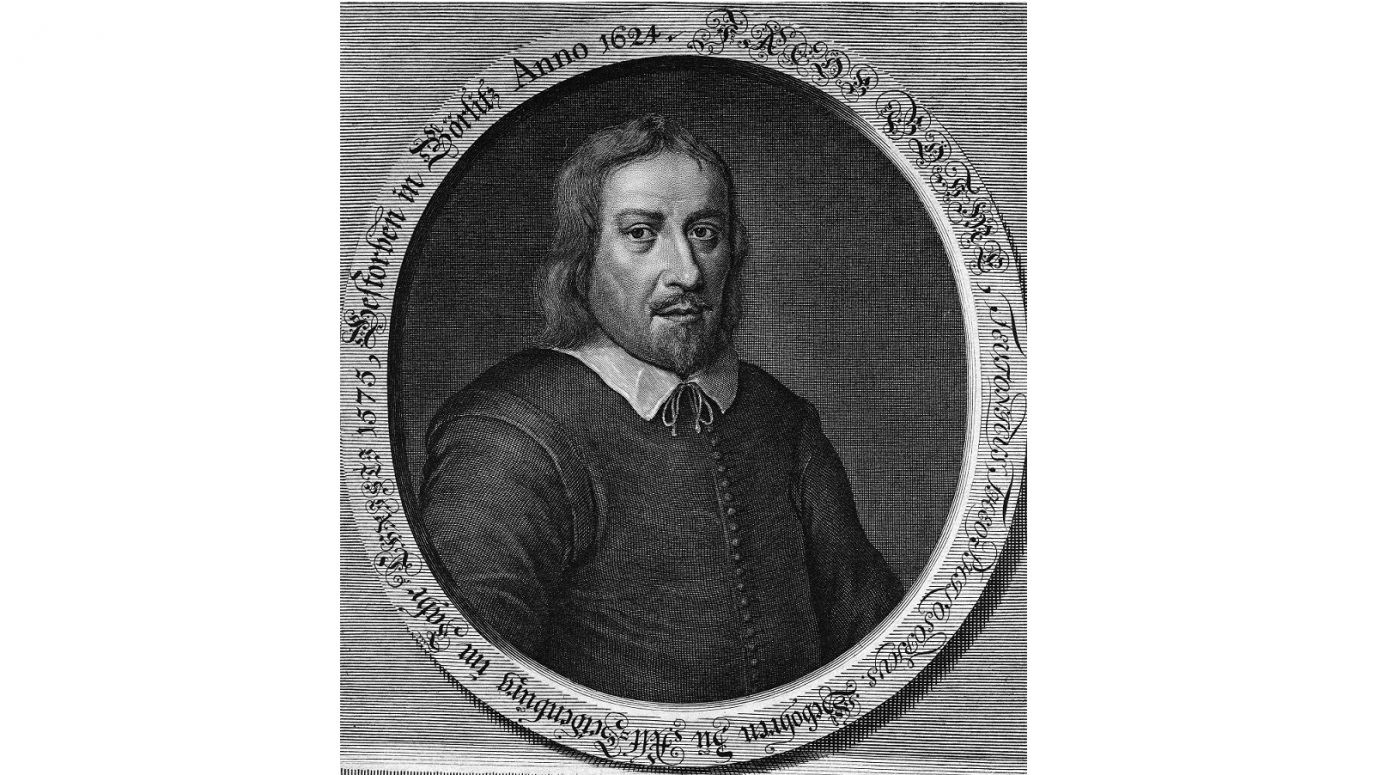

The title appears dry and unengaging. We could be forgiven in thinking that this is an academic work in a boring academic style, aimed at a narrow readership. It’s not like that at all. However. Koyré describes his subject, an ordinary craftsman from the Lusatian region, with a degree of passion, as a subject who became a European cultural trendsetter.

Before this happened, the visionary had to overcome difficult obstacles and it’s in this book that we can discover exactly why and how.

Böhme was a Lutheran protestant whose writings angered the local protestant clergy. In Poland the opinion took hold that the chief perpetrator of religious inquisition in Europe, at any rate, was the Roman Catholic church. But in the seventeenth century at least the Protestant faiths, of whichever shade, were also far from religiously tolerant. Earlier, the pyres were burning in the theocratic Geneva of Jean Calvin. Böhme was to experience this painfully too.

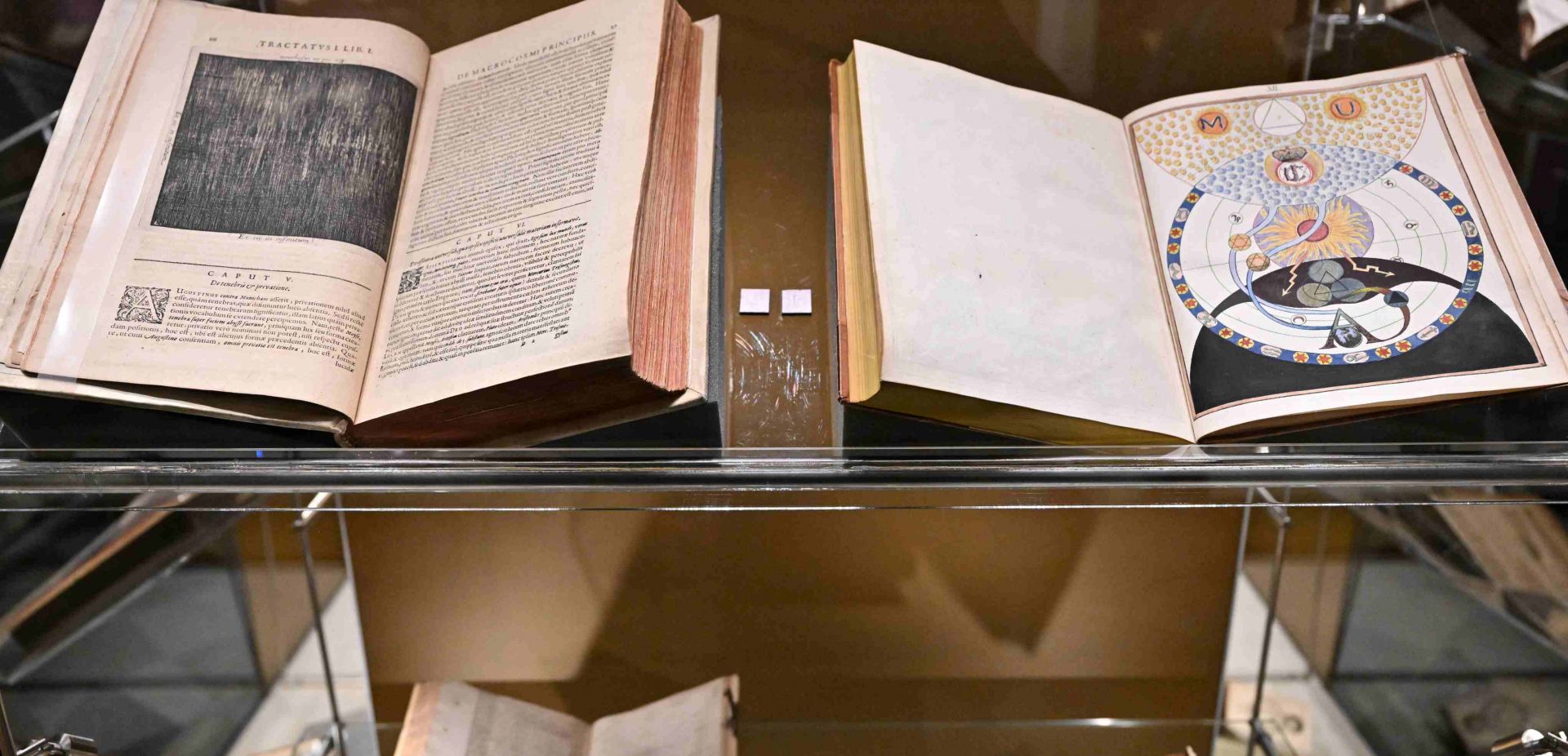

He may be connected to the Baroque era , but fashionable intellectual tendencies from the earlier Renaissance were influential. Böhme was interested in alchemy and it was this that aroused the suspicion of the Protestant clergy that he entered into nefarious dealings with magic.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

Gregorius Richter, a leading pastor, the pastor primarius, in the town became his chief accuser. He counted on being able to expel Böhme from the place, although this proved to be unsuccessful. But he didn’t mince his words in the meantime. An example: ”You despicable blabbermouth, you blasphemer. Let those who have also read your writings get away from here. Begone, and never come back. Die like an animal!”

The mystic defended himself against these attacks by the clergyman, who wished to compromise him. “The Primarius is criticising my books, to which he has the right, but first he ought to read them, which he hasn’t done.” Above all he refused to renounce his Lutheran faith in front of all assembled. “I do not avoid the church, I attend it. Neither do I show contempt for the sacraments, I accept them. I only acknowledge that the church of Our Lord Jesus Christ is within us”.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE  Gregorius Richter, a leading pastor, the pastor primarius, in the town became his chief accuser. He counted on being able to expel Böhme from the place, although this proved to be unsuccessful. But he didn’t mince his words in the meantime. An example: ”You despicable blabbermouth, you blasphemer. Let those who have also read your writings get away from here. Begone, and never come back. Die like an animal!”

Gregorius Richter, a leading pastor, the pastor primarius, in the town became his chief accuser. He counted on being able to expel Böhme from the place, although this proved to be unsuccessful. But he didn’t mince his words in the meantime. An example: ”You despicable blabbermouth, you blasphemer. Let those who have also read your writings get away from here. Begone, and never come back. Die like an animal!”