A Pole who wanted to be Ukrainian

25.05.2022

His choice did not meet with the approval of the Poles, who considered it an act of betrayal. He was also in conflict with the Ukrainian nationalists.

He was a loner and, in some ways, an eccentric who failed in his dreams about an independent Ukraine, at the beginning of the 20th century. Who is this about? Wacław Lipiński – historian, sociologist and politician, a Polish nobleman from Volhynia, who decided to become... Ukrainian.

His life story is elucidated by two books. One of them is a monograph “We, the Ukrainian nobility” (“My szlachta ukraińska”, 2006) by Bogdan Gancarz, a historian, journalist, editor of the bimonthly “Arcana” and the Krakow edition of “Sunday Guest” (“Gość Niedzielny”). The second book is a novel “Oblivion” (“Zapomnienie”, 2016, Polish translation – 2019) by Ukrainian writer Tanya Malarchuk.

Although the books are not new, they are worth mentioning. The current events in Ukraine raise questions about the validity of Lipiński’s thought.

He lived during a turbulent period. Born in 1882, he witnessed the decay of the old world: the collapse of the great monarchies that shared the territory of what is now Ukraine.

The First World War brought an end to the power of the Habsburgs and Romanovs. Many nations inhabiting their empires aspired to independence and sovereignty. The Poles succeeded in achieving their goal and the reborn Republic of Poland became a reality. The Ukrainians, meanwhile, fared much worse.

For a certain period – between 1918 and 1920 – they tried to become politically independent. First, the Ukrainian People’s Republic (UPR) was established. It was supported by the Central Powers. Then it was replaced by the Hetmanate established under German patronage, modelled on the monarchical system. Its leader was the former adjutant general of Tsar Nicholas II, a descendant of Ukrainian hetmans Pavlo Skoropadski. When the Empires centraux capitulated in the war, the UPR returned, but had to face new challenges.

The Ukrainians tried to gain statehood for themselves by forming an alliance with Poland (a pact between Józef Piłsudski and Symon Petlura, the chairman of the UPR Directory) against both the Reds and the Whites (the communist Bolsheviks and the anti-communist forces). Ultimately, however, nothing came of it. In this matter, the Bolsheviks proved stronger by installing the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in Kyiv.

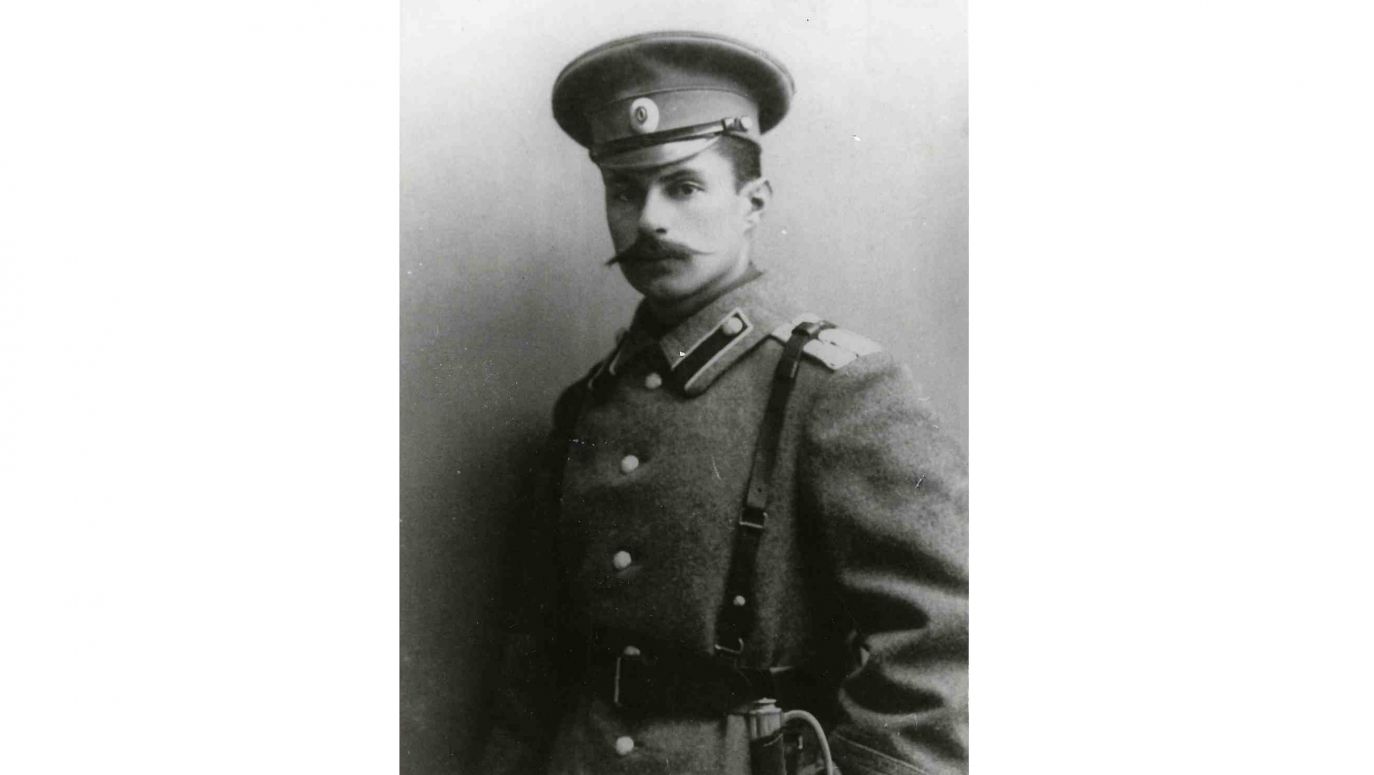

Wacław Lipiński was a graduate of Jagiellonian University. Already as a student he was involved in activities for the independence of Ukraine. Later, as a conservative and a monarchist, he supported the Hetmanate. It was this state that appointed him its ambassador in Vienna. After the collapse of the Hetmanate, he continued his mission in favour of the UPR. He resigned from his post in June 1919. But he remained in exile and continued to promote Ukrainian independence ideas. He spent the rest of his life mainly in Austria where he died in 1931. He wrote his texts in Polish and Ukrainian.

Lipiński’s choice of Ukrainian identity could not meet with the approval of Poles, who saw it as an act of treason. After all, the struggle for the existence or non-existence of Polishness took place under the Partitions of Poland. Lipiński did not get on with his wife either – his marriage broke up. He also failed to convince his daughter of his Ukrainian identity. So what was Wacław’s reasoning behind changing his name to Wiaczesław?

Tania Malarczuk reconstructs (or quotes) Lipiński’s words spoken in Krakow in 1903: “I am a Ukrainian Pole. My language is Polish and my faith is Catholic. I do not renounce my language nor my faith and I do not intend to do so. And yet, I feel obliged, as soon as the Ukrainian nation is formed, to take its side. This is not a romantic pipe dream, as many people believe, but a question of logic and political expediency”.

So what was Lipinski’s guiding principle? It was the programme of “territorialism” he formulated. This concept assumed that a person’s identity is defined by the land to which he is belongs, and not by his ethnicity. Lipiński was therefore convinced that the Polish noble families in Ukraine were in fact Ukrainian nobility, and that they were linked to the Ukrainian people by a common territory.

Such views antagonised him not only with Poles, but also with Ukrainian nationalists. His main opponent was their leading guru Dmytro Doncow. Lipiński, as an advocate of Christian universalism, rejected the absolutisation of ethnic particularisms.

On the one hand, the thinker from Volhynia was devoid of nostalgic sentiments towards the feudal past, but on the other, he was critical of the modernising transformations. As a result, state societies, ruled by cosmopolitan blue blood, were transformed into nations. The era of mass democracy was dawning.

Meanwhile, Lipiński spoke out against the ethnic unification of Ukrainians. Ukrainian nationalism excluded people like him from the society, i.e. cultural Poles rooted in Ukraine.

Lipiński’s polemic with Roman Dmowski was interesting. The main theoretician of Polish nationalism in “Thoughts of the Modern Pole” (1903) set the following conditions for Ukrainians: “If the Ruthenians are to become Poles, they must be polonised; but if they are to become an independent Ruthenian nation, capable of living and fighting, they must be told to acquire what they want to have through hard effort, and toughen up in the heat of battle”.

As we read in Bohdan Gancarz’s book, such proposals aroused Lipiński’s serious concerns. According to him, if the task of “toughening up” the Ukrainians were to be carried out, it would have to be undertaken by the Ukrainian nobility, i.e. cultural Poles. And this would condemn them to antagonistic relations with the Ukrainian people, because instead of solidarising with them, they would show them a sense of superiority driven by nationalism.

Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny – one of those heroes who would have to be dreamt up if they did not exist.

see more

In the interwar period in Poland, Lipiński’s oeuvre enjoyed the recognition of the philosopher Marian Zdziechowski (“To Kill a Priest. The Church Hinders Revolutionaries”). In the essay “The conservative element in Ukrainian ideas” (“Pierwiastek zachowawczy w idei ukraińskiej”) from 1937, he commented on the conservative-monarchist ideas of the thinker from Volhynia. The latter was an advocate of a hierarchical society model, a “classocracy”, which in Ukraine would be legitimised by the Hetmanic tradition originating in the Cossack uprising of Bohdan Khmelnitsky. Lipiński did not look at that uprising as a bloody mob rebellion. He saw the events of the 17th century as a state-creating movement of the Ukrainian nobility.

Zdziechowski summarised Lipiński’s message as follows: “Which way should the road to this ‘classocratic’, Hetman-like Ukraine lead? So far, one has never heard of a state being born out of a rebellion of the lower classes; they can destroy the state, but they will not create it; it can only be created by an active minority in which the chivalrous spirit of the ancestors is alive, i.e. the nobility and those who by their actions become nobility”.

After the First World War, however, it turned out that this could not be achieved in Ukraine. In 1926, in “Letters to Farmers”, Lipiński gave vent to his bitterness by making a brutal diagnosis of the situation at the time. He stated that his homeland was “divided between two kingdoms of the same devil”. He sketched a vision in which “in the West, democracy prevailed (...) and with it came the reign of gold and churlishness”, while “in the East, a nomadic, plundering and destructive horde took power”.

Lipinski’s conservatism and monarchism may seem anachronistic today. And yet, the figure of the thinker fascinated Tanya Malarchuk, a representative of the young generation of Ukrainian literature immersed in the culture of postmodernism. At the same time, the writer made in “Oblivion” – which, by the way, was honoured with the BBC Ukraine 2016 Book of the Year title – a trick worth mentioning: while exploring Lipinski’s biography, she dealt with herself, weaving autobiographical threads into the work. At times, while reading the work, this exploitation of her personal issues may even come across as narcissistic and pretentious.

But “Oblivion” is first and foremost a novel about Lipinski. And in this respect it is a fascinating book. It is likely that Lipiński intrigued the young writer by the fact that he was an outsider all his life – someone whom contemporary culture, fetishising exuberant individualism, admires.