Coppola's work carries an important warning: The "success" of a family can be the road to its disintegration.

see more

Reymont’s novel was published in episodes in 1922, on the pages of “Tygodnik Ilustrowany”. And as a book it was released in 1924. After WWII, quite significantly, it hadn’t been reissued and it was veiled in silence. It would only come to pass that somebody mentioned it briefly, e.g. Józef Rurawski, the biographer of Reymont who, in 1977, called it a “lampoon of the revolution”.

The historian of ideas Dariusz Gawin rightly noticed that in the Polish People’s Republic (Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa, HRTA the PRL) literature textbooks there were attempts to take the master of Polish naturalism’s heritage to the advantage of the leftist tradition. In this context, he pointed to Reymont's most famous novels, namely “The Peasants” (“Chłopi” – awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1924) and “The Promised Land” (“Ziemia Obiecana”) stating: “the Nobel Prize winner's great works were meant to show the difficult life of the Polish people and to expose the ruthless nature of capitalism emerging in Polish lands”.

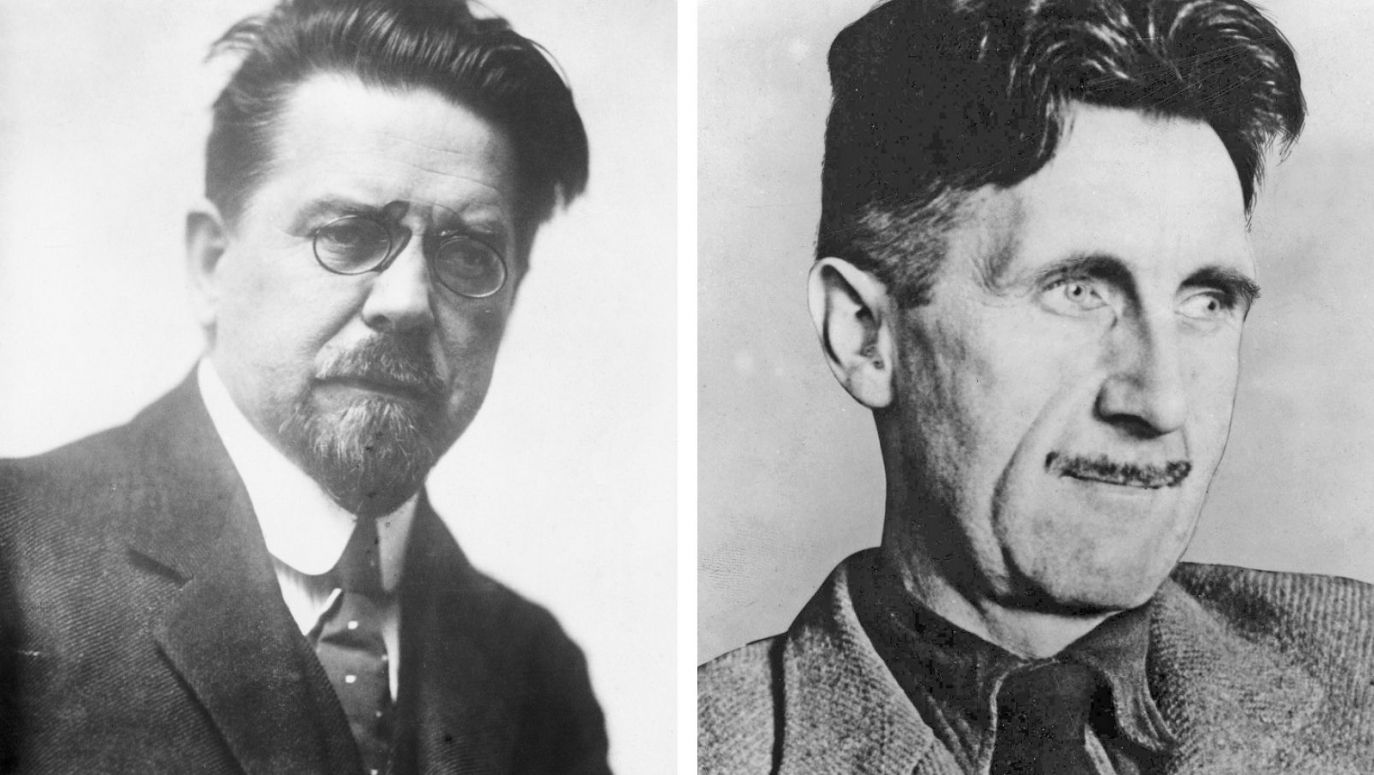

Obviously, under the PRL regime facts regarding writer’s political involvement that deemed inconvenient for the communists were ignored. Before WWI Reymont had been a member of the National League (Liga Narodowa). Over many years – until his death in 1925 – he had been friendly with Roman Dmowski. He was therefore close to the National Democracy (Narodowa Demokracja/ND) movement, even if by the end of his life he joined the Polish Peasant Party (Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe) “Piast”. By no means then was he a leftist (as opposed to Orwell, although he, having socialist views, also defined himself as an anti-communist after all).

Political movements, wherewith Reymont was in any way connected, had to take a stance in the face of conflicts tearing apart capitalist societies. However, they rejected the class struggle postulated by the communists and put forward the program of social solidarity as an alternative to it. They preferred the national interest to both the left-wing (class) and liberal (individualist) perspective.

From today’s perspective, the issues Reymont brought up in his “Revolt” may seem a thing of the past. However, the writer focused on timeless problems. Usurpation as towards God – and that’s how the attempt on the order of nature should be perceived – as well as succumbing to lies are no phenomena unique to the 20th Century. Since the beginning of time, having to choose between good and evil, people have always been put to some test.

– Filip Memches

TVP WEEKLY. Editorial team and jornalists

– Translated by Dominik Szczęsny-Kostanecki