The global battery industry, which is critical to the success of the climate transition, depends on three key materials: nickel, lithium and cobalt. And those create new difficulties and dependencies. As early as 2028-33 the world economy will be hit by a cobalt crisis. Will “gas blackmail” and “petroleum crises” be replaced by new, lithium-cobalt ones?

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

In 2001 alone the world allotted USD 1,1 trillion to the pursuit of this state; the leader in these expenditures is China, which spent as much as USD 546 billion, which is more than the EU and the US combined (USD 180 and USD 141 billion, respectively). These amounts will only grow, because the powerful machine of climate policies is just getting started, and its goal is to build a new economic paradigm based on the principle “who emits – has to pay”.

In 2001 alone the world allotted USD 1,1 trillion to the pursuit of this state; the leader in these expenditures is China, which spent as much as USD 546 billion, which is more than the EU and the US combined (USD 180 and USD 141 billion, respectively). These amounts will only grow, because the powerful machine of climate policies is just getting started, and its goal is to build a new economic paradigm based on the principle “who emits – has to pay”.

"Putin is losing the European market and has to sell fuel to China and India, offering substantial price discounts. And this hurts," says Andrzej Krajewski, author of the book "Oil. The blood of civilisation".

see more

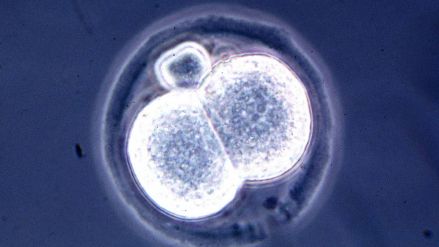

They can be used for toxicity tests and drug analysis

see more