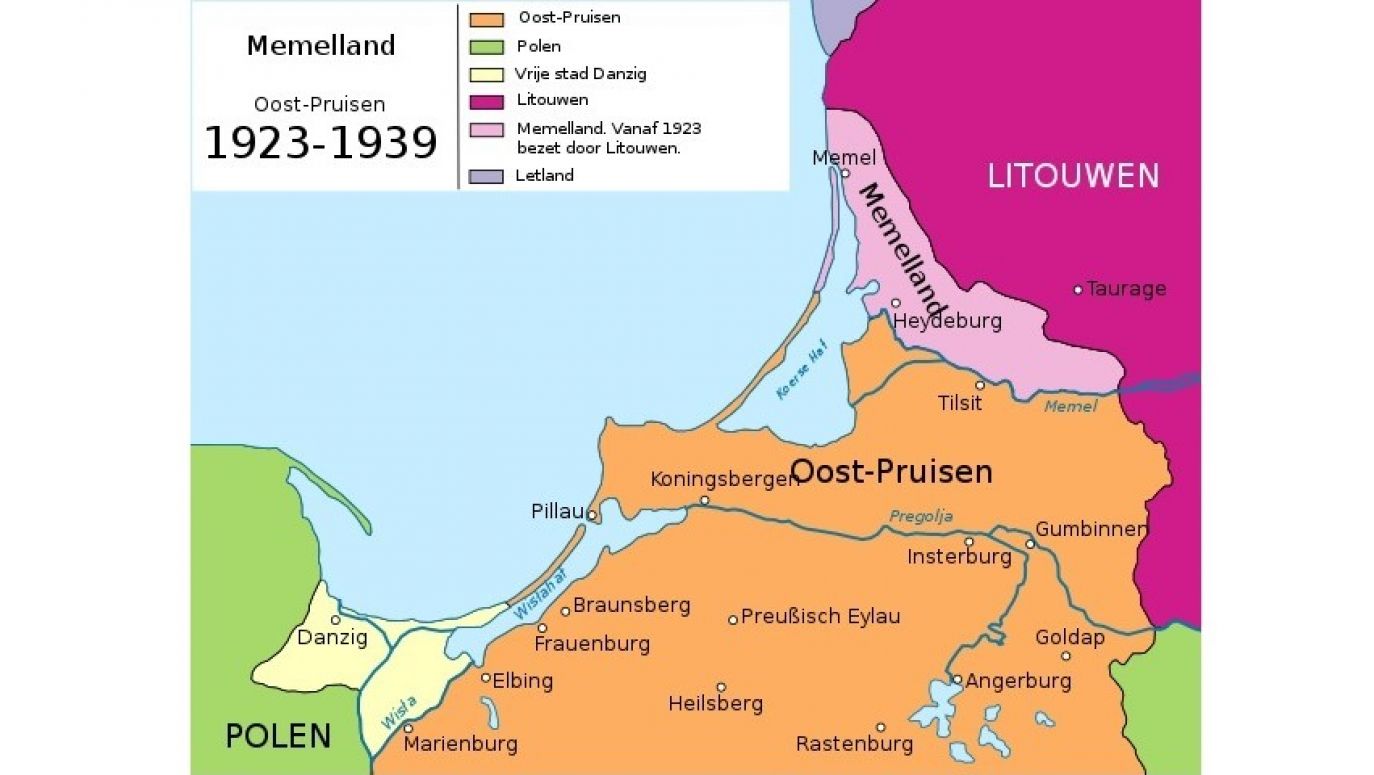

On Wednesday 10 January, French and Belgian troops began to enter the Ruhr valley – and a few hours later, when the telegraphs were already rattling all over the place, the Lithuanians started an uprising in the Klaipėda district!

The uprising, hmm... There were a few dozen local volunteers, the rest were regular soldiers, police officers and members of the paramilitary Shaulis formation. Preparations began in December 1922 – and the funniest thing is that General Silvestras Zukauskas and the head of military intelligence, Colonel Jonas Polovinskas, who prepared the whole action, were directly modelled on the Żeligowski’s Mutiny of October 1920! But what does it mean – the common traditions of the Grand Duchy…

The Kaunas government took care to create clandestine, civilian political structures: Committees for the Salvation of Lithuania Minor were set up everywhere in Klaipėda Region: the Committee was headed by Martynas Jankus. At the same time, the head of the Shaulis’ structures, Vincas Mickevičius, made contact with the then head of the German Reichswehr, General Hans von Seeckt – and, having assured him that no German citizens or German property would suffer during the uprising, obtained permission to purchase one and a half thousand carbines, five machine guns and one and a half million rounds of ammunition from the Reichswehr’s warehouses.

A strike from Tauragė

So excellently armed, the “volunteers” under the command of Colonel Polovinksas (in those days, by the way, he changed his name to “Jonas Budrys”, which sounded more “Lithuania-Minor-esque”) took up their starting positions at Kretinga and Tauragė stations on the Lithuanian side. Having stripped themselves of their Lithuanian documents, money, cigarettes and matches, and instead pulled on their arms the tricolour bands in the colours of Lithuania with the letters MLS (Mažosios Lietuvos sukilėlis, Lithuania Minor Volunteer), they entered in three columns, striking towards Klaipėda, westwards, i.e. towards the border with East Prussia, and north-eastwards, towards the sea.

Who was actually going to resist them and why? The French did not fancy dying for Danzig, why should they put their heads up for Klaipėda? On the morning of 11 January, the whole circle, apart from the main city, was in their hands. High Commissioner Gabriel Petisné refused at the first moment to surrender the city – so a dozen rebels and two Frenchmen were killed in a shootout. And then, although the Polish gunboat “Commander Piłsudski”, the British cruiser “Caledonia” and two French torpedo boats stood in the roadstead – the Lithuanians captured the city.

The Entente could not afford to be cornered, so the first reactions were angry: on 17 January the Council of Ambassadors set up and sent to the Baltic a Special Commission, which on 26 January demanded that the rebels leave Klaipėda, repeating this demand even more emphatically on 2 February.

The Great Reversal

In reality, however, no one wanted a conflict. Neither Britain nor France were prepared to commit further military forces, and it was realised that the Soviets’ tacit support for Lithuania could then turn into active support – and no one was prepared for a new war in the East.

And moreover – the thought of the Great Reversal was maturing. The Poles have taken Vilnius, right? And they are unlikely to give it up? And the Lithuanians are boiling with anger because of this, and it is a bit hard to surprise them? And it would be worth finally approving these borders in Eastern Europe and stop worrying about the whole thing, wouldn’t it? But what if…

On 4 February, the Council of Ambassadors changes its front and – unofficially at first – makes a brief proposal: Klaipėda for Vilnius. The Lithuanians will get access to the sea – and everyone will be happy.

Kaunas protests, of course: after all, it cannot officially accept the loss of its historic capital! But in fact everyone is happy: in May 1924, the Klaipėda Convention was signed and the entire district, on the basis of autonomy, became part of the Republic. Even the Germans came to terms with this, signing a border treaty with Lithuania in 1928.

Of course – they had reconciled by the time. But that already belongs to the pre-history of the Second World War, which everyone knows.

–Wojciech Stanisławski

TVP WEEKLY. Editorial team and journalists

–Translated by jz

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE