They were young, talented, in love with art, willing to experiment and to make sacrifices, ready to have fun and to work hard. They referred to themselves as the Brotherhood of St. Luke (the so-called “St. Luke’s Men”; an art group, active 1925-1939, drawing from 16th and 17th century painting traditions, specialising in historical compositions, landscapes, portraits, genre and biblical scenes). The world was open to them because they had received a government commission for paintings about Polish history for the World Exhibition in New York. In February 1939, their seven large paintings sailed for America – they did not return to Poland until July 2022.

– For my grandfather, after the war, it was not the worst thing that these paintings might never come back, but that they all, i.e. the St. Luke’s Men, already had their lives finished, “settled” – historian Adam Michalak, grandson of Antoni Michalak (1902-1975) from Kazimierz on the Vistula, one of the protagonists of this story, tells TVP Weekly. The other protagonist of this unusual and complicated story is Kazimierz itself, this wonderful city of painters and other wizards.

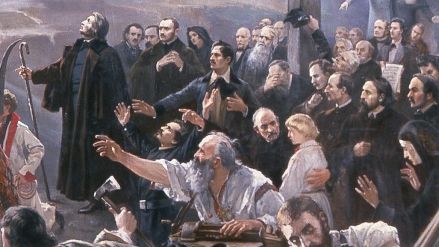

Kazimierz became famous among the artistic fraternity long before the Brotherhood of St. Luke appeared with its easels, stretchers and paints, but above all with its dedicated ethos of earnest work on perfecting one’s painting craft, and with the custom of accolading painters almost in public, in a colourful procession, in joyful – though taken very seriously – festivities.

Brotherhoods of this type were one of the ways of returning to tradition in inter-war Europe, so one of Antoni Michalak’s grandsons, Jan (also a painter), even wrote his doctoral thesis on the subject, “On the need for new figurative painting resulting from the romantic experience of reality: reflections on painting in the European art circle, with particular reference to the tradition of the Brotherhood of St. Luke”.

Like a medieval guild

The St. Luke’s Men group was formed in 1925 by: Bolesław Cybis, Jan Gotard, Aleksander Jędrzejewski, Eliasz Kanarek, Edward Kokoszko, Antoni Michalak, Jan Podoski, Mieczysław Schultz, Czesław Wdowiszewski, Jan Wydra and Jan Zamoyski; they were later joined by Bernard Frydrysiak, Jeremi Kubicki and Stefan Płużański. The group’s mentor – writes Izabela Mościcka on the website lukaszowcy39.pl – and main theoretician was Tadeusz Pruszkowski, their favourite teacher from the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, who had a very strong influence on the work of his students.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

Pruszkowski was also known for his other tastes, such as flying in an aeroplane from Warsaw to Kazimierz, which – as one can guess – must have been quite a sensation, even in a town accustomed to the artistic extravagances of its guests. A fellow of most excellent fancy, one might say.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE