Marc Chagall – Freak from the Shtetl

27.07.2022

The word “luftmensz” appears in Yiddish (“airman” in English). It means someone whose head is in the clouds, someone obsessed, a dreamer and mystic. And it was Chagall who painted various “luftmen”. Because, in a way, he was one of them.

Before World War I, he studied painting in Vitebsk, St. Petersburg and Paris. And it was in the capital of France that he came into contact with the avant-garde phenomenon, including Cubism.

He then returned to his hometown. He witnessed the changes brought about by the Bolshevik Revolution. When the Leninist regime took over in Russia, he even briefly became the commissar of fine arts in the Vitebsk region. But ultimately, he did not find a place for himself in the first communist country in the world. As an artist, he did not fit into the new reality. The subjects of his work differed from the expectations for art put forward by the Soviet authorities.

Chagall was a freak from the shtetl, difficult to tame for any political officer. The painter's mentality is revealed, for example, in the paintings Fantasy Scene Against a Pink-Green Background or Yellow Billy Goat in the Countryside. Both show processions of characters who were mentally close to the artist.

The word “luftmensz” appears in Yiddish (“airman” in English). It means someone whose head is in the clouds, someone obsessed, a dreamer and mystic. And it was Chagall who painted various “luftmen”. Because, in a way, he was one of them.

When it comes to his attitude towards communism, it can’t be ruled out that the painting The Visit of Moses and the Golden Calf in the Studio is a clue in this matter. In it we see a scene from the Book of Exodus: God’s chosen people indulge in an act of idolatry. The golden calf is the false god. Only here it is red, associating it with communism.

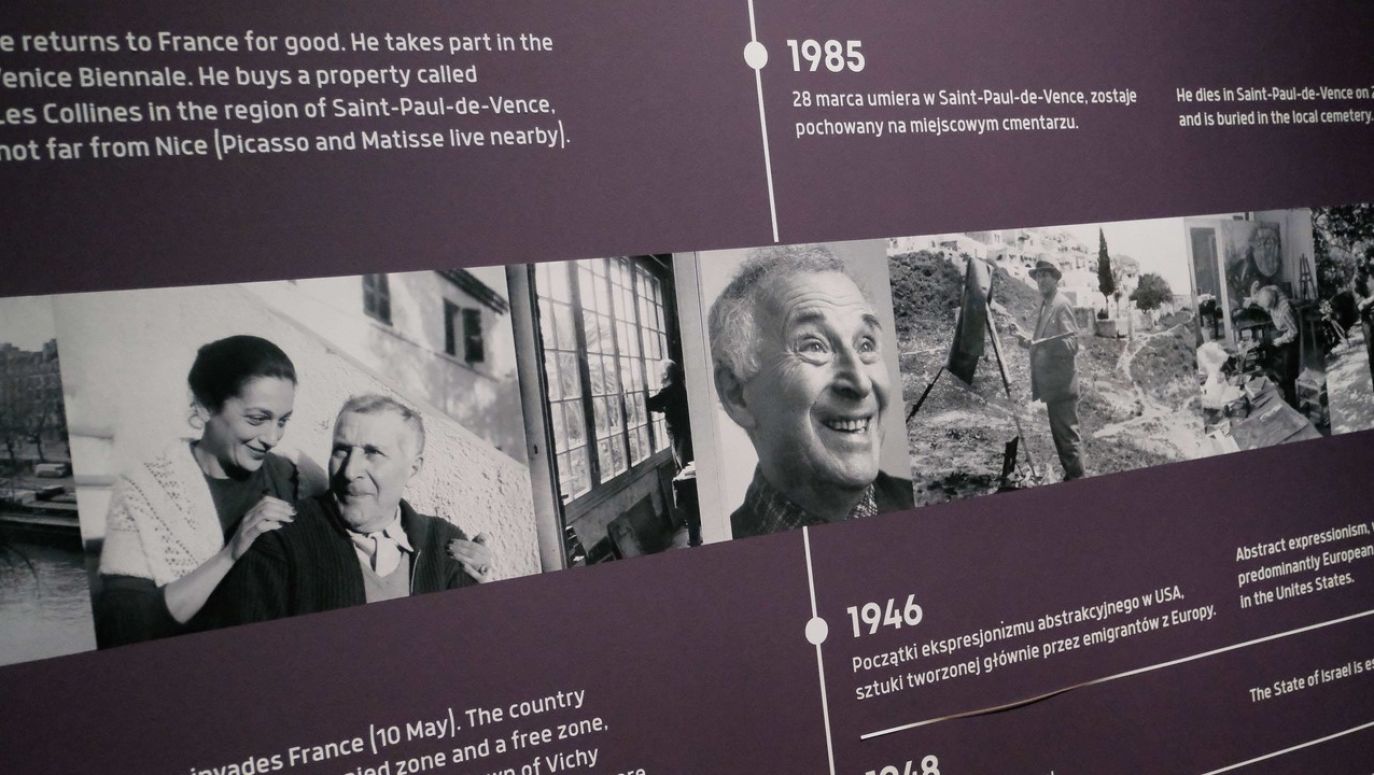

In 1922, Chagall emigrated to the West. He purposefully settled in France. From 1937 onward he was a French citizen. When his new homeland came under German occupation during World War II, he took refuge from the Holocaust in New York. In 1948, he again moved to France. He lived to a ripe old age, dying when he was nearly 98 years old.

The encounter of Judaism with faith in Christ may seem surprising in Chagall's work. And it is in vain to look for traces of any Jewish prejudices against Christianity in the artist's oeuvre.

It is worth paying attention to, for example, the painting ‘My Life’ between Vitebsk and Paris. It presents a man and a woman, a couple in love, thus the author of the work and his wife Bella, as well as the synagogue in Chagall’s hometown and landmarks of the French capital, the facade of the Notre Dame Cathedral and the Eiffel Tower. It is significant that on the tower... Christ is crucified.

And when it comes to the Passion theme, this is not an exception in the painter’s work. After all, we can point to another work by Chagall, under the all-telling title The Crucifixion.

In turn, Christ appears in a specific context in the painting Around the Book of Exodus. Chagall recalls a certain story: in 1941, a group of Jews, threatened by the Holocaust, attempted to flee from Romania to Palestine. The ship they were on, however, sank. Christ, dying on the cross, accompanies them in this event. He suffers just like they do.

However, I will allow myself to interpret this work in a way that did not occur to the author. Perhaps the Holocaust turned out to be a preview of what awaits Christians in the future. It concerns persecuting them as misfits in a world where believing in Christ is foolish or scandalous.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE