Usually, the belief is that poets have their heads up in the clouds and despise everything connected with money. The decision by the Polish Sejm [the lower chamber of the Polish Parliament] to proclaim the year 2022 as the Year of Polish Romanticism offers everybody a good opportunity to verify this stereotype.

Of the four Bards of Polish Romanticism, Adam Mickiewicz, the author of "Pan Tadeusz: The Last Foray in Lithuania"[transl. by Bill Johnston, New York, 2018], had the poorest childhood. When his father, a lousy lawyer from Nowogrodek, died, his wife and four young sons were left almost destitute. Adam, used to poverty from a young age, never managed to come into a fortune. He never manage even to get his own residence. He always lived at some friend’s place, or in cheap boarding houses, rented rooms or servants’quarters. While working as a teacher in Kowno [Kaunas], he complained in a letter to a friend: "My money is always tight". During his travels, he used to leave financial matters to his companions. He also gladly took advantage of the hospitality offered by the owners of manors and palaces.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

His forced departure to the east [in 1823 he was arrested and deported to Russia for illegal patriotic activities] marked the beginning of what proved to be the most luxurious period in the poet's life. Pampered by ladies and cherished by the Russian elites, he held court in their drawing rooms and toured Crimea in the company of loyalists and agents of the secret tsarist police. Influential friends even got him a job in the office of the governor-general of Moscow. However, coming to his senses and having obtained permission to go abroad ("to save his health"), he fled to Europe.

For a year and a half, he was stuck in Rome, where his money ran out. Friends would always come to his rescue, offering him non-refundable loans or supporting fictitious investments that invariably somehow would be forgotten. Of course, the bard earned money by publishing his works, but the cash never stuck to him -- whatever he earned, he immediately handed over the surplus to his countrymen who were in greater need. Moreover, in order to gain permission to enter France as quickly as possible, he even waived his right to a political emigrant’s allowance.

On the Parisian pavement

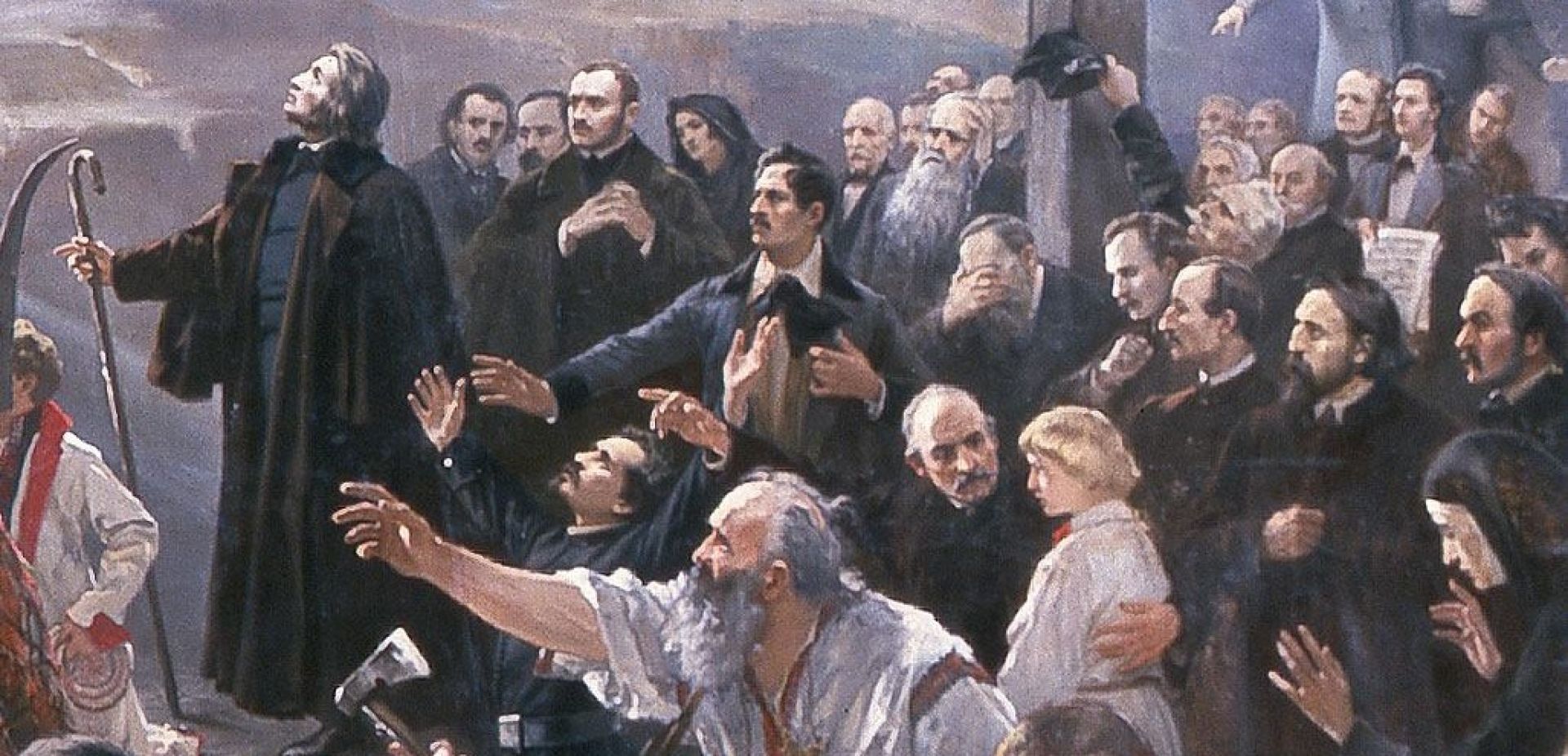

After the failure of the November Uprising [also known as the Polish–Russian War 1830–31], Polish patriots flocked westward. More than half of the 10,000 refugees chose France not as a new homeland,but as a place to await the war they were confident would bring the Polish state back to life. Without exagerration, these refugees represented the nation's elite, and poets were the elite of the elite, even though most of them never smelled any gunpowder.

Who could have predicted that the world conflict they all dreamt of would not occur for another 80 years? Malnutrition, poor housing conditions, forced inactivity and the gradual decline of hope for a return to theire home country had an impact on the exiles’ health. Tuberculosis literally decimated their numbers. The former masters had to work physically, which in a way explains their radicalization. With the exception of the group that centered around the Hotel Lambert [the grand Parisian townhouse belonging to Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski wherein the political faction of Polish exiles associated with him used to gather], the rest of the emigres drifted further and further to the left.

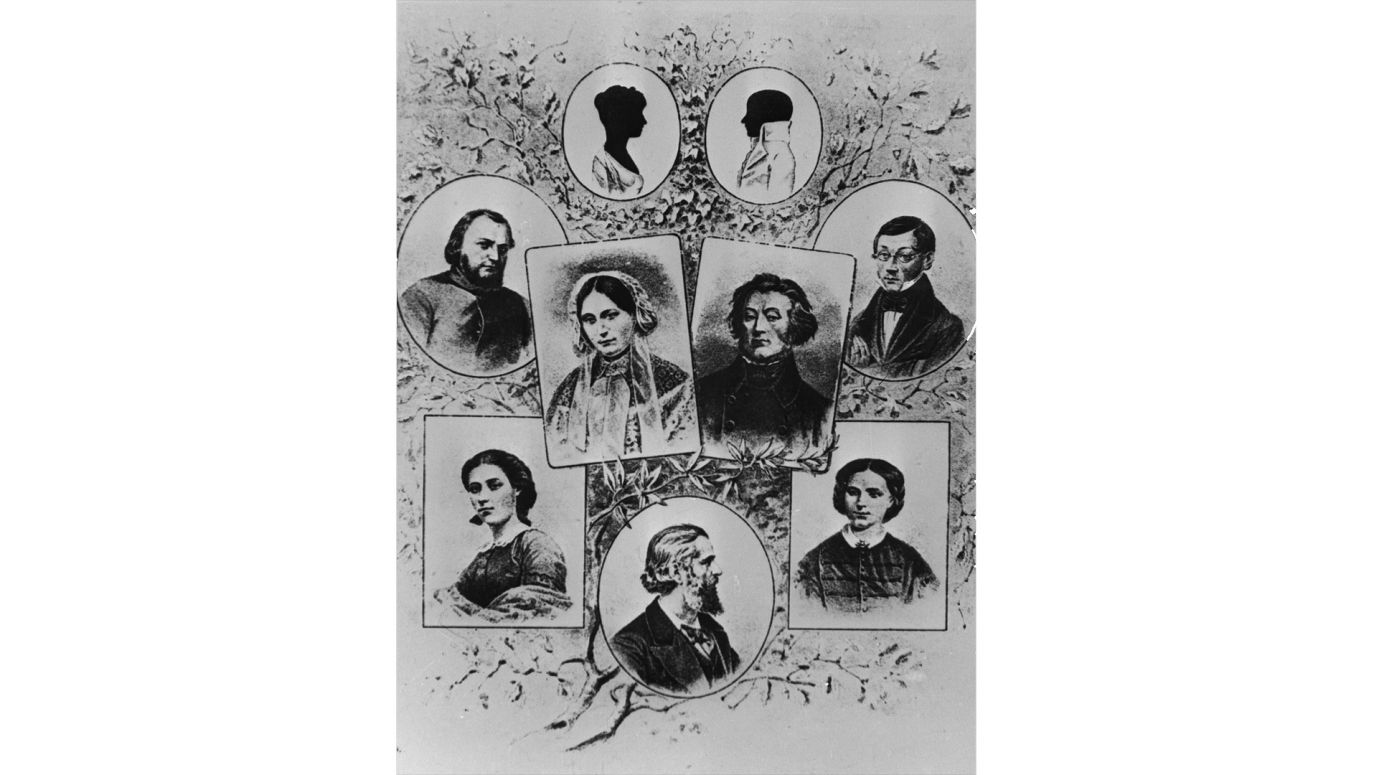

A favorable marriage might offer salvation from the downward slide. However, neither youth, the will to fight "for your freedom and ours", nor poetic fame were viewed as advantages in the eyes of potential parents-in-law. Mickiewicz avoided becoming an old bachelor by marrying an orphan without a dowry. His wife Celina was as carefree about finances as he was. "We don't have a penny of fixed income and we don't expect to have it," she informed her friends. Adam wrote plays about the history of Poland, but Parisian theaters were reluctant to put them on. He was the editor of the "Polish Pilgrim" but wasn’t being paid for it. In the end, the bookseller and publisher of his works, Eustachy Januszkiewicz, took on responsibility for overseeing his countryman’s finances.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE