The Kremlin’s Tricks Towards the Vatican

06.04.2022

Representatives of Russian Orthodoxy from the Soviet Union accepted the invitation to the proceedings of the Vatican II Council. Mackiewicz describes how through various intrigues they led the Ukrainian Uniates to give up on highlighting the persecution of the Greek Catholic church in the USSR. The price of their silence was the release by the Soviets of the Greek Catholic metropolitan of Lviv, Josyf Slipyj, who had been locked up in prisons and labor camps for 17 years.

2022 is the Year of Józef Mackiewicz. 1 April was the 120th anniversary of the writer’s birth.

The position of the Vatican on Russia’s attack on Ukraine caused confusion among Catholics in Poland. This is attested to most of all by columnists associated with the Catholic Church. They are the ones pointing at Pope Francis’s restraint in judging the Kremlin’s actions.

It is indicative that in this matter divisions that come to the surface during various disputes are fading away. Various groups like “Christianitas” and “Więź” are also making their disappointment with the message of the Holy See known.

There is not much to say, the successor to Saint Peter – in accord to some extent with the quasi-pacifist line that he took during his pontificate – refuses to assert, that the battle of the Ukrainians against the Russian occupier is a just war. The Holy Father’s statements are replete with generalities condemning the spilling of blood, but a clear indication is missing of who is the aggressor and who is the victim in the conflict taking place in Ukraine.

In one voice with Lukashenko and Putin

From the Polish point of view, the eastern policy of the Vatican could have already caused consternation last November. At the height of the migration crisis on the Polish-Belarusian border, a press conference took place in Moscow with Russia’s chief diplomat, Sergei Lavrov, and the secretary for relations with states in the Holy See’s Secretariat of State, Archbishop Paul Gallagher.

The Vatican dignitary did not utter a word about the migration wave from Asia, set in motion by the Lukashenko regime, being a tool for a hybrid attack against Poland, Lithuania and Latvia. While he did declare objections to the actions of the Polish authorities towards people breaching the Polish-Belarusian border. In his opinion they were not sufficiently humanitarian.

Archbishop Gallagher’s narrative turned out not only to benefit the dictator of Belarus, but also the Kremlin. Both Belarusian and Russian politicians promote the image of Poland as a country of “fascists” (which, moreover, harmonizes with the message broadcast across the world by various leftist and liberal groups, namely that Poland is a nation of anti-Semites and racists).

You might get the impression that the Vatican’s current eastern policy contrasts with what was done by Saint John Paul II, who was considered an enemy of the Soviet Union by the Kremlin. In the 1980s, the Holy See was aiming for the same goal as the United States and the United Kingdom. The option chosen by the leaders of these two countries – President Ronald Reagan and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher – a hard line against the USSR, was supported by the Polish pope. The stakes at the time were the fall of the evil empire.

All due to Aggiornamento

That is why the criticisms made against St. John Paul II by the writer Józef Mackiewicz, might come as a surprise. In his commentaries he accused the papacy of seeking compromise with communism after World War II.

Today, the problems discussed by Mackiewicz in the books "W cieniu krzyża" ["In the Shadow of the Cross"] (1972, on the pontificate of Saint John XXIII) and "Watykan w cieniu czerwonej gwiazdy" ["The Vatican in the Shadow of the Red Star"] (1975, on the pontificate of Saint Paul VI) or the text published in 1949, “Bolszewizm i Watykan” ["Bolshevism and the Vatican"], are strictly songs of the past. Although the Soviet Union has been gone for 30 years, nevertheless, the relations between the Holy See and Russia mean a great deal to Poles.

Regarding Mackiewicz’s opinion on Saint John Paul II, he expected that he (and from Blessed Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński) take a confrontational political course towards the Polish People’s Republic, the price for which would have mainly been borne by the Church faithful in Poland.

The thing is that the strength of Christianity is not only in the courage to profess your faith (in certain circumstances even at the risk of one’s life), but also prudence (especially when you are responsible for what might happen to other people).

We have to consider, however, that Mackiewicz was looking at the Church’s reality – including in the Eastern Bloc countries – through the eyes of a political emigre, since he lived in the West from 1945 onwards. He was an uncompromising anti-communist, which suitably defined him (Adam Michnik described this position as “dull, zoological anticommunism”). But it is also not without meaning that back in the interwar period, as a young man... he converted from Catholicism to Orthodoxy. Apparently, he was induced to do so by the demolition of Orthodox sanctuaries by the Sanacja governments (Sanation, polish political movement created by Józef Piłsudski in the interwar period) in the Chełm Land in the late 1930s, which could birth the assumption that his decision was founded on shallow, political motivation.

A picture emerges from Mackiewicz’s “Vaticanological” books of the Church as a institution that changes at the bidding of a broad, worldwide, leftist front, increasingly influential in the academic and cultural spheres. The pontificate of Saint John XXIII, begun in 1958, turned out to be a turning point. The trademark of this pope was aggiornamento (updating). The term was meant to mark the renewal of the Church. Its peak was the Second Vatican Council, lasting from 1962-1965.

If the renewal of the Church took place exclusively in the liturgical and pastoral dimension, it probably would not have bothered Mackiewicz. The thing is that aggiornamento had serious political consequences, in the face of which the writer could not remain indifferent.

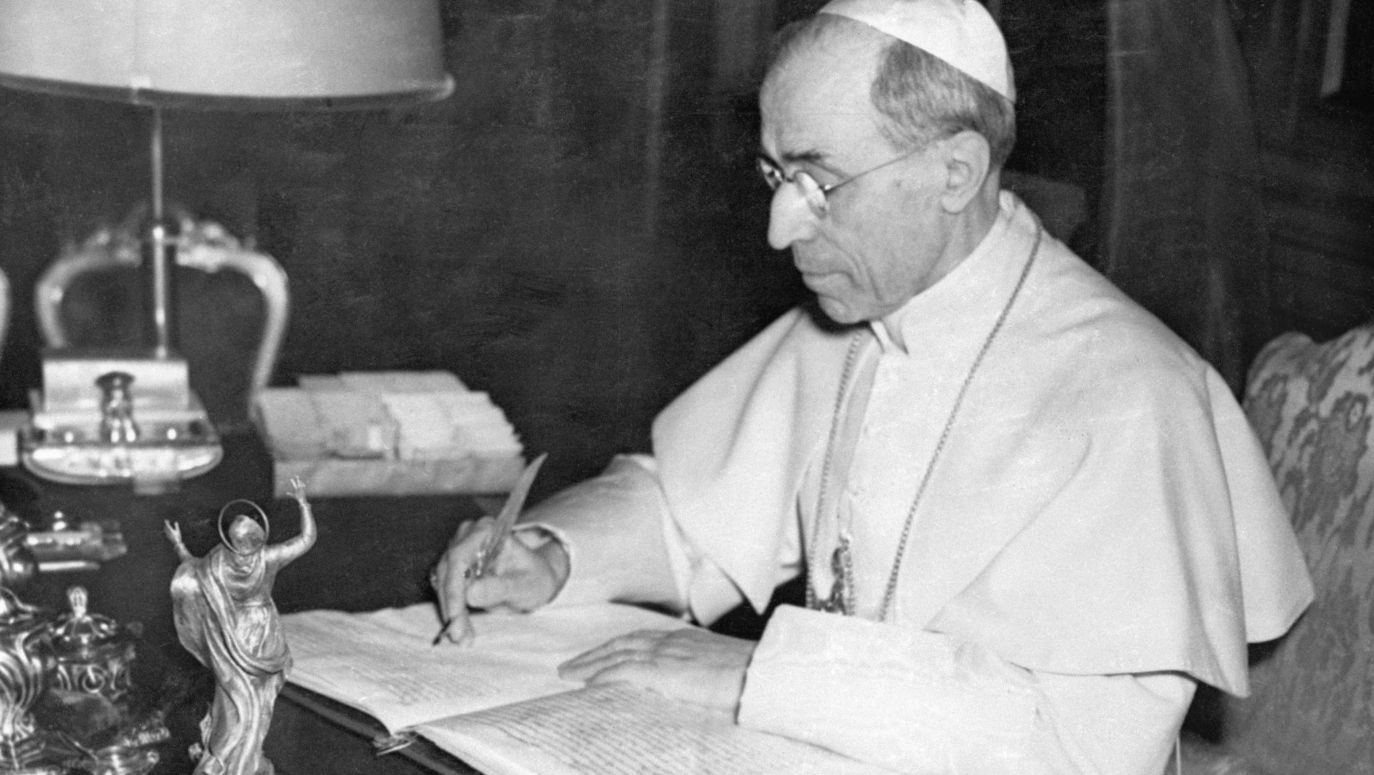

In taking up dialogue with modernity, the Holy See turned out to be conciliatory towards those powers that it had been in conflict with earlier. Therefore, along with the pontificate of Sain John XXIII, the time of popes condemning communism as a godless ideology and manifestation of metaphysical evil, ended (Mackiewicz mentions the “crossing out” of Pope Pius XI’s encyclical “Divini Redemptoris” from 1937.

Before, during the pontificate of Pius XII, the Vatican did not avoid colliding with the interests of the USSR – the power appearing on the international arena with the aura of the conqueror of “fascism.” Mackiewicz cites the communiques of the Holy See from 1952, where it was clearly stated that it does not know “peace at any price” and recognizes only “just peace,” which was its commentary to the slogan “Peace” bandied around by the Kremlin.

The words of Pius XII cited by Mackiewicz, spoken on Christmas Day 1954, are meaningful: “Slowly, in place of the Cold War, a state of relaxation is entering, as if giving a mutual guarantee gave a moment of respite, which is called, not without irony, ‘cold peace’... Pacifist efforts from the side of determined renegades against God, are always highly questionable valuables and do not serve to reduce the sense of anxiety or to remove it entirely from the earth. If they do not serve as a tactical cover for the purpose of, in essence, creating anxiety and chaos.

According to Mackiewicz, the pope “seemed to be warning against the ease of coming to an agreement, or to misunderstanding-in-an-understanding with someone, who strives towards completely different ends and only wants to, aided by an illusory agreement, fool us.”

Intrigues of the Moscow patriarchate

However, these warnings did not stop the Vatican from changing priorities afterwards. Its primary concern became caring about world peace, but conceived in such a way that it resulted in concessions towards the Soviet Union. The Holy See began to take at face value the assurances of political dignitaries from Moscow, that, the USSR does not want any wars.

In effect, the Church was more or less coddled by the worldwide communist movement under the direction of the USSR. Thus the Kremlin could count on its agents, so the Moscow Patriarchate of the Orthodox Church, which tightened ecumenical contacts with the Vatican.

Mackiewicz describes the games played by the representatives of Russian Orthodoxy from the Soviet Union, who accepted the invitation to the deliberations of the Vatican II Council. Through various intrigues they led the Ukrainian Uniates to give up on highlighting the persecution of the Greek Catholic church in the USSR. The price of their silence was the release by the Soviets of the Greek Catholic metropolitan of Lviv, Josyf Slipyj, who had been locked up in prisons and labor camps for 17 years.

During Soviet times, the Moscow Patriarchate also played a vital role for the Kremlin, opposing the “proselytizing” of the Church in the USSR, which was understood as a postulate limiting the missionary activity of Catholics in the Soviet Union. We must note that – what Mackiewicz could not have noticed, since he died in 1985 – that after the collapse of communism and the fall of the Soviet Union, the state of affairs remained the same. For this reason, Saint John Paul II plan for a pilgrimage to Russia was not realized.

It begs the question, how would Mackiewicz interpret the position of the Holy See towards the current policy of the Kremlin? Would he be fooled by Vladimir Putin’s propaganda about Russia being the guarding traditional – so, after all, anticommunist – values?

The last citizen of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

We must note that Mackiewicz was a Russophile. In the tsarist Russia of the early 20th century, he saw a European country, based on Christian morality, respecting private property and free competition – a political entity which the USSR was the total negation of. In the book Zwycięstwo prowokacji (1962, Triumph of Provocation), he compared the Romanov empire in its later phase to Portugal. He believed that the Russian nation was a victim of the Bolshevik coup.

But communism is not only an ideology abstracted from concrete social realities. In practice, it is also an emanation of historical, geographic and cultural conditions, in which it is implemented. In this sense, Bolshevism, even if it annihilated masses of Russians, was a natively Russian phenomenon.

One of the works that reveals Mackiewicz’s emotions towards tsarist Russia, is “Kontra” – an impassioned story about Don Cossacks, who found themselves in exile in western countries after the revolution in 1917. During World War II, the fought alongside the armies of the Third Reich against the Soviet Union, in the hope of liberating its nation from the yoke of communism. After the defeat of Germany they wanted to come to an understanding with the Americans and British. But they treacherously handed over to the USSR.

In “Kontra,” it is striking how sympathetically the Polish writer treats the Cossacks. Yet we are talking about the group that brutally pacified Polish patriotic demonstrations during the January Uprising against Russia in 1863(the longest lasting insurgency in post-partition Poland), for example.

Might an explanation be that Mackiewicz did not consider himself as a patriot of the Polish state but of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania? And as his nationality he ironically and perversely declared: “anticommunist.”

Returning to the “Vaticanological” commentary of the writer, it is not a question whether he was right or wrong in the judgments he passed regarding the Church. Certainly, Mackiewicz’s theses are very controversial. But they are based on rich, factual materials, which cannot be taken dismissed. And which give us a lot to think about, also in the context of current events.

– Filip Memches

–Translated by Nicholas Siekierski