With a knife, pillow, snuff box. How to kill a tsar

30.03.2022

Overwhelmingly, European “political regicides” were carried out publicly. The perpetrator boasted about their crime or performed penance for it, sometimes living out the rest of their days, more often themselves perishing at the hands of an avenger. They were always called by their true name however – both the perpetrator and the act of murder.

These questions are also appearing for another reason however: the awareness of how often in Russia the ruler was murdered by his closest entourage – while this act was not so much the result of personal revenge or rivalry, but a tool of stabilization or correction of the system of power.

I only emphasize these circumstances since only they allow for the experience of Russian history to be properly distinguished from European history, where hundreds of regicides occurred after all. It started with Julius Caesar (though really much earlier), while – daggers, swords and the blades of guillotines flashed, from which, as Jacek Kaczmarski sang lamenting Louis XVI, “necks crunched in underwear.”

Raising their hands against crowned heads, assasins (both of sound mind and insane), anarchists and Dominicans, they were liquidated through political trials (Karol II), the fell at the hands of execution squads – from Byzantium to London, from the castles of early Frankish rulers (it is estimated that to the times of the relative stabilization of the Carolingians, around 40 crowned heads were killed at the hands of their rivals on the territory from the Pyrenees past the Rhein) past Polish Gąsawa, where Prince Leszek the White perished in 1227.

Unknown Perpetrators

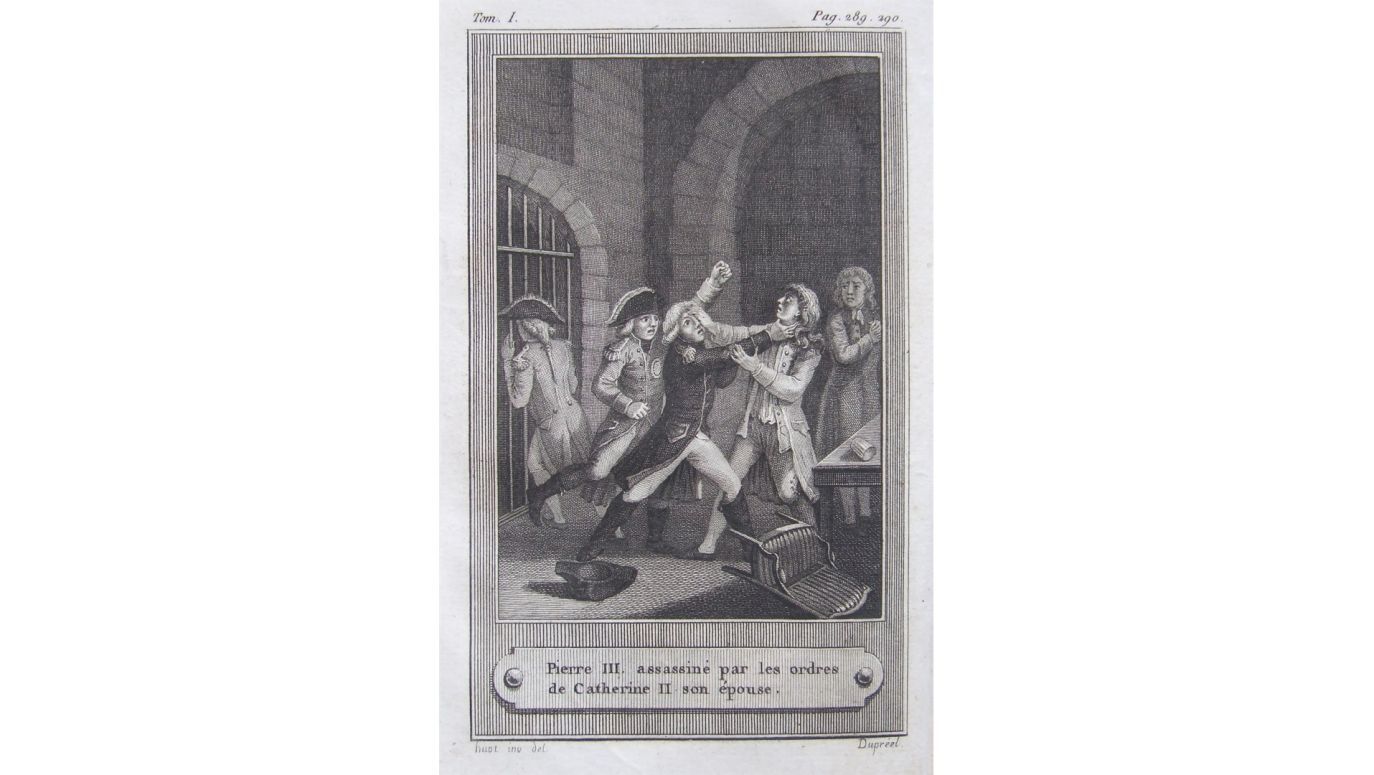

Even if we separate the deaths at the hands of a madman, an explicit enemy or a jealous wife – European “political regicides” were overwhelmingly carried out in public. The perpetrator boasted about their crime or performed penance for it, sometimes living out the rest of their days, more often themselves perishing at the hands of an avenger. They were always called by their true name however – both the perpetrator and the act of murder. Of course it could happen like in Hamlet, a brother poured poison into his brother’s ear, simulating a natural death – and up to the present day we are not aware of some of these deeds. Otherwise, how else would the authors of successive, sensational history books make a living?

Still, the rule (which can be explained by both the European fondness for truth, and the permanent political disintegration of the continent, its incurable pluralism) was to reveal the masterminds, perpetrators and circumstances of an assassination. Russia is something different. The Boyars still chopped up Prince Andrey Bogolyubsky in 1174, as was the custom then. But later – later just a secret wrapped in a mystery, tongues ripped out, witnesses sent to hard labor and no nighttime conversations among fellow countrymen.

And it all started with Tsar Dmitry.

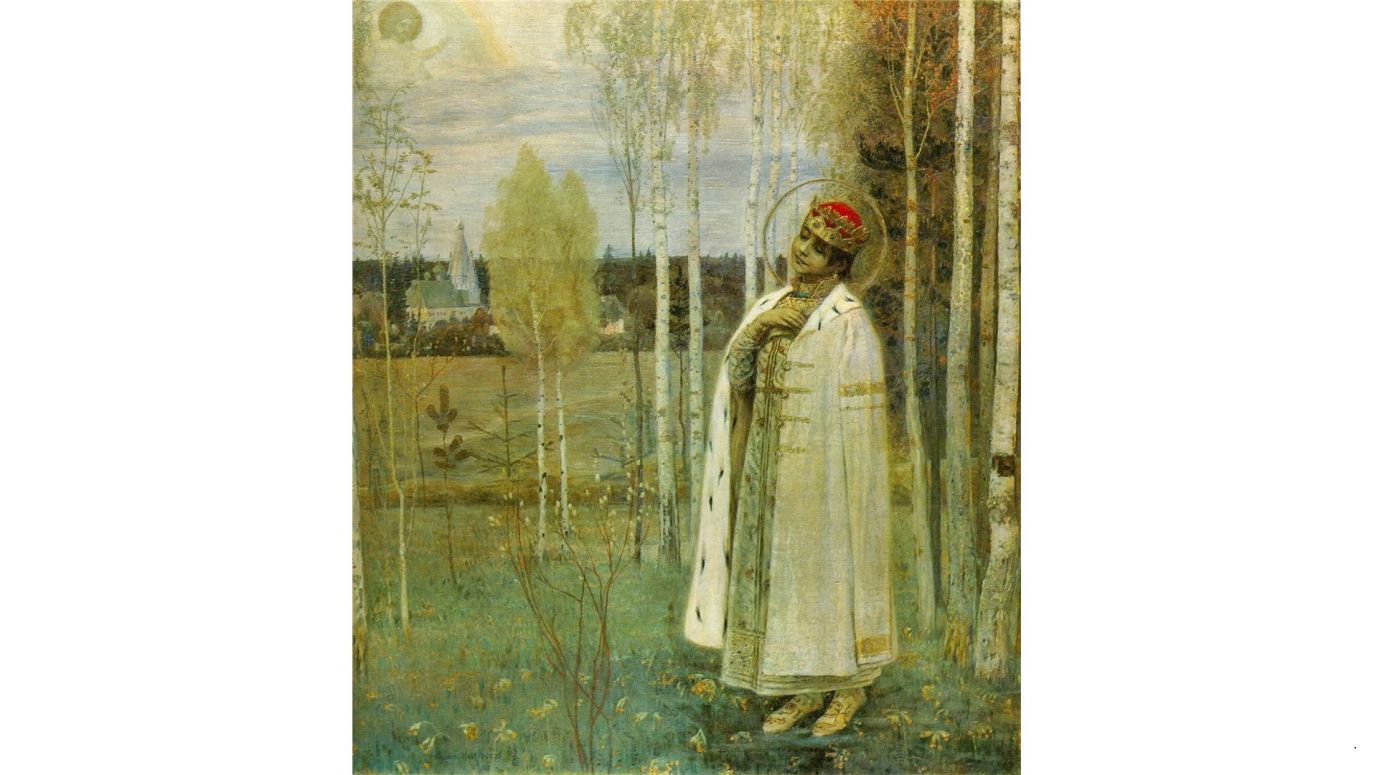

It was lovely, boyish and innocent, strolling through the birch grove in an ermine fur coat, fair-haired and bright-eyed (at least on the Mikhail Nesterov’s sentimentalizing painting from 1899), because according to the account of one of the first English travelers to Muscovy in those days, John Fletcher, he rather took after his father, Ivan the Terrible: “they say that he likes to curiously watch as sheep have their throats cut and that he himself joyfully beats geese and chickens with a stick until they drop” – reports Fletcher in the treatise On the State of Muscovy.