Fidel Castro’s great victory. How Cuba outplayed the Soviets in Africa

16.03.2022

Castro made one of the craziest decisions of his life. He sent literally everything that he had to Angola. So, thousands of soldiers, planes, armaments, ammunition and medical supplies set off for Africa. Hardly any soldier remained in Cuba, the island was totally defenseless.

Angola, 1987. The civil war in Angola will end shortly, though no one knows this at the time. Not then, nor for many years thereafter, did anyone know how far on the defensive the Soviet Union had been. At the time, Cuba took full control in Southern Africa, removing the Soviets from all decision-making. Whether they wanted to or not, the Kremlin had no means of exerting pressure on Havana. The truth of what the Cold War was like in the south of Africa did not see the light of day for many years.

The Cold War was defined by the fact that the United States and the Soviet Union – though they were not in direct combat – financed the opposing sides in various conflicts around the world. The first so-called proxy war, so a surrogate war, was the Korean War. The conflict in Angola also became a surrogate war.

The Cuban Landing

Angola declared independence on 11 November 1975. Already several years earlier, three main political parties had formed in the country: the MPLA, UNITA and FNLA. By the end of 1975, in principle only the first two mattered, yet the communist MPLA managed to occupy the capital (Luanda) and seize power. Opposing this, UNITA declared war against the MPLA right after independence was announced.

The MPLA, headed by Agostinho Neto (and from 1979, Jose Eduardo dos Santos), was a leftist party that did not hide its sympathies towards the Soviet Union. Standing in opposition to them was UNITA, which was not only a political party, but a military organization, led by Jonas Savimbi. UNITA was betting on cooperation with the West and counted on help from the US to overthrow the Marxists from the MPLA.

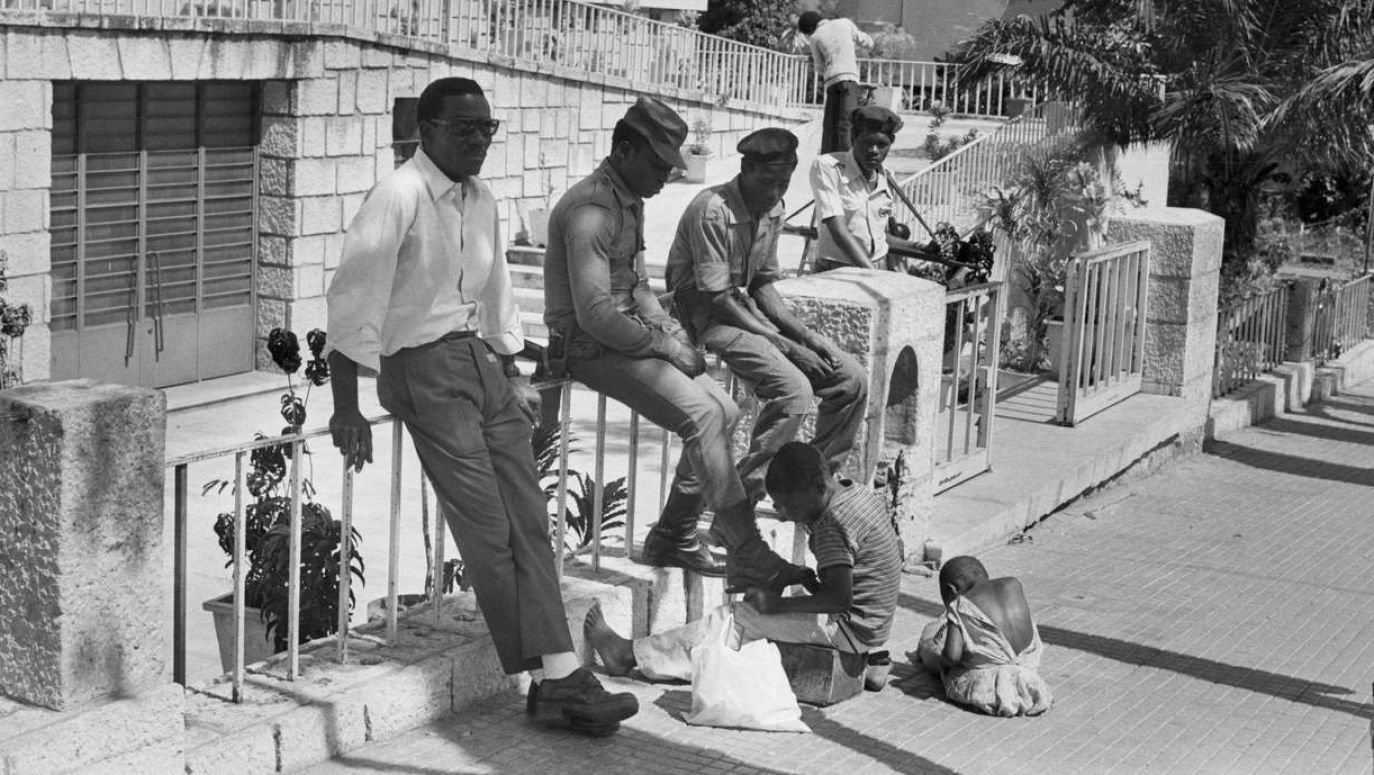

In November 1975, all signs pointed to the conflict between UNITA and MPLA becoming the next “classic” African civil war. Then everything changed when, several days after Angola declared independence, the first Cuban soldiers arrived in Luanda.

Contacts between the MPLA communists and the Cubans had already been established in the mid-1960s. Before the MPLA even took power, it was agreed that the Cubans would come to Angola to train MPLA units and help them take (or maintain) power. So, in mid-November, the Cubans landed in Luanda.

The presence of the Cubans in Southern Africa redefined the balance of power in the world. Washington was shocked and the Republic of South Africa (RSA) fell into a panic. Presumably, Moscow was no less surprised. Although the leader of the USSR, Leonid Brezhnev, knew of “certain” plans by Fidel Castro towards Africa, he discouraged him from any official military involvement. “Revolution cannot be exported from one country to another by force of arms” – Castro is to have said. The Soviet Union remained a threat, but it was not the same USSR as before. Moscow understood that expansion does not depend on waving the “Communist Manifesto.” It was believed that this was precisely what Castro intended to do.

Meanwhile, the Cubans arrived in Africa well-equipped and ready for battle. Among them were military personnel of various ranks, including generals. There were also plenty of doctors, equipment, medical supplies and weapons. Castro was ready for war.

The decision to send troops to Angola was his own idea. For many years however, he persisted in the view that Moscow had wanted it and the Cubans were their puppets. A thorough analysis of various sources though, clearly indicates that the Cuban dictator independently made the decision to go to Angola.

Politicians (even in the USSR), and later many historians, could not comprehend that Castro could send his people to Africa for ideological reasons. However, that is exactly what happened. Fidel Castro honestly believed in his anti-imperialism, his battle with capitalism, and that he would overthrow the racist, apartheid governments of South Africa.

Along with the arrival of the Cubans, the United States – being certain that Moscow was behind it all – intensified their financial and military aid to UNITA. South Africa also supported this organization. Angola became the new front of Cold War conflict.

On one side was the MPLA, the Cubans and the Soviet Union, which, whether it wanted to or not, became involved in the civil war in Angola. On the other side was the UNITA, the United States and South Africa. The conflict was further complicated by the war for independence in neighboring Namibia, which had been going on since 1966. Namibian activists, concentrated in the SWAPO organization, cooperated with the MPLA, thus standing with the communist bloc.

South Africa felt cornered. If it allowed the MPLA to stay in power in Angola, and gave up Namibia (which it had de facto occupied since 1915) to the Namibians in SWAPO, it would mean being surrounded by countries sympathetic towards Moscow. Pro-war rhetoric in the country was very strident. The South African military joined the civil war in Angola by the end of 1975.

Nobody knows where the president is, there are protests in the streets and Russian flags flying.

see more

All Forces and Money

The civil war in Angola lasted for many years. Although the Americans and the Soviets did not send their soldiers there, both countries supplied their partners (UNITA and MPLA) with money and military gear.

Soviet military advisers also appeared in Luanda who tried to take the lead and command at the front. Their results were mixed – most of the initiative came from the Cubans, who convinced the Angolans to their side.

Cuba engaged all of their forces and essentially all of their financial resources into the war in Angola. More troops were sent to Africa. At the peak, over 40,000 Cubans were stationed in Angola. On top of this, thousands of civilians came to Angola: civil servants, doctors and teachers. At the same time, Cuba took in thousands of Angolan children. On the island they could freely attend school, far from the war. This element in particular was widely utilized by Havana in its propaganda.

Of course Cuba was dependent upon the Soviet Union. Havana counted on financial and military aid from the Soviets. As long as Leonid Brezhnev ruled in the Kremlin, a broad stream of support flowed to Angola. The situation changed in 1982 after Brezhnev’s death.

At the time – which must be remembered – the Soviets were fighting in Afghanistan, having entered it in 1979. So that is where Moscow’s attention was concentrated. For successive Soviet leaders who took the reins after Brezhnev, Afghanistan was the main focus. Supporting Angola became an unfortunate necessity. Moscow, however, did not know how to exit the conflict. Mikhail Gorbachev, the next Soviet leader, was very skeptical towards the war in Angola, yet he still agreed to finance the MPLA.

In the meantime, South Africa sent increasingly larger forces into Namibia. Battles with the Namibian SWAPO insurgents were intensifying. At the same time, South African troops militarily supported the Angolan UNITA, which in the mid-1980s, controlled south-eastern Angola. Money and weapons also flowed from the United States.

The Soviet General’s Defeat

The situation on the Angolan front stabilized at the turn of 1975-1976 and for nearly ten years afterwards, it hardly changed. With South Africa’s help, UNITA controlled the south-east of the country, and the rest of the territory was dominated by the MPLA and the Cubans.

In September 1985, one of the largest offensives by the communist forces took place. It was a result of Soviet pressure. The leader-coordinator of the Soviet operation in Angola, General Konstantin Kurochkin, believed that the South African resistance in south-eastern Angola (the Cuando Cubango region) could only be broken through a large offensive. The issue of commencing operation “Second Congress” generated severe conflict between the Soviets and the Cubans. Ultimately, the Cuban commanders agreed to the Soviet plan. But the operation ended in total failure and UNITA and South Africa forced their opponents to retreat to their earlier positions.

The Cubans, including Fidel Castro’s close associate and right hand in Angola, Jorge Risquet, decided to cut off Soviet decision makers. Starting at the end of 1985, mostly Cuban plans were put into practice, namely the training of small units for fighting in the bush. Moscow did not understand the realities of warfare in Southern Africa. Soviet advisors, including Kurochkin, believed that the only effective way to fight the UNITA and South African forces was a massed attack with a strong army backed by tanks and other heavy equipment. These tactics had no chance to prove themselves over the long term. Partisan fighting, introduced by the Cubans (in which they were experienced), was the most effective method.

At the same time, Havana was pressuring Moscow to send more MiG-25 and MiG-29 fighter planes to Angola, so that the Cubans could achieve air superiority over South Africa. Eduard Shevardnadze (then the USSR’s minister of foreign affairs), who spoke to Fidel Castro about it, said that Moscow could supply the planes, but the Cubans would have to promise that while fighting with South Africa they would not cross the border with Namibia, which South Africa treated as an integral part of their country. Castro did not intend to make any such promises. Shevardnadze was noticeably irritated.

From that time onward, Cuba increasingly sent signals that after defeating UNITA they intended to enter Namibia and fight for that country’s independence, which made Washington and Pretoria very nervous each time it happened. Moscow eyed its Cuban ally with increasing distrust, yet it counted on its ability to hold back Castro’s wild plans if they cut off weapons deliveries to the Cubans. However, as it turned out, even when the Soviets stopped supplying the Cubans with equipment, that did not stop them.

Hundreds of millions of bottles streamed into Germany. Many wineries made fortunes.

see more

For the months that followed, all of Havana’s requests for greater military aid from Moscow were left unanswered. Since, at the time, intensive diplomatic activity was going on between the United States and the Soviet Union. The leaders of both powers met several times. Thus, the Soviets did not want the increase of deliveries to Angola to destroy the altogether decent atmosphere of discussions with the Americans. Castro, however, was furious, believing that the Kremlin intended to sell out Angola’s autonomy and Namibia’s independence behind their backs by making a deal with the US.

The Cuban dictator carried out his own policy. He was active in the Non-Aligned Movement. In 1986, during a meeting of the leaders of countries belonging to this organization, he shared that Cuba had no intention of withdrawing from Africa – as far as Angola wished it – as long as apartheid existed in South Africa. In practice, this meant that the Cubans intended to fight for Namibia’s independence, and even – who knows – bring about the toppling of the government in Pretoria. At least that is how his declaration was understood in the West. Castro was considered an unpredictable person, capable of doing anything.

Cuito Cuanavale

In mid-1987, Soviet general Kurochkin proposed another offensive against south-eastern Angola. The Cubans were again strongly opposed, believing that the previous attempts, particularly the last offensive two years earlier, were failures. Kurochkin was uncompromising however, making it clear that this was the only way that Moscow would send more equipment to Angola. The operation did not make much sense militarily, but for the Soviets it practically became a matter of “honor” – they had to prove to the Cubans how wrong they were.

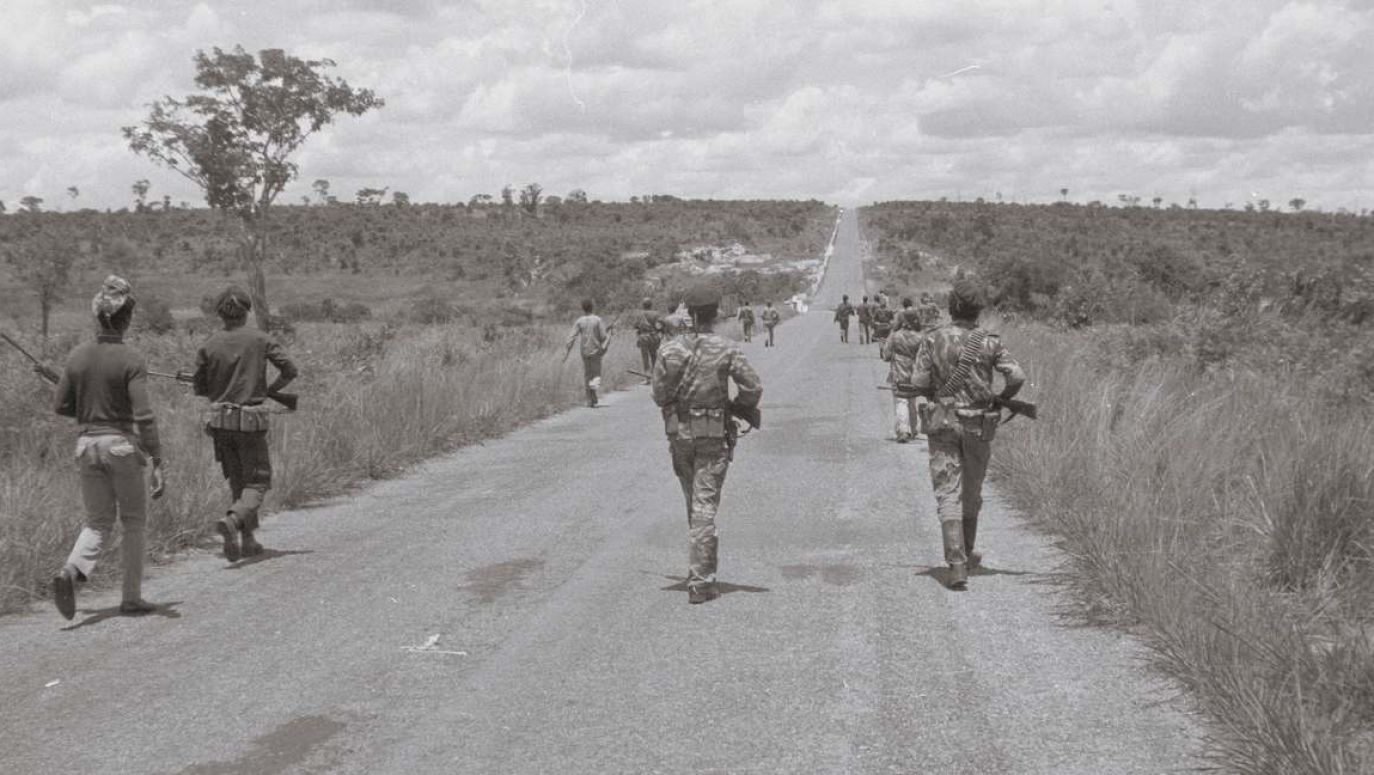

On 12 July 1987, operation “Salute to October” began. This time the Cubans, supported by the Angolan MPLA government forces (and unofficially, Soviet soldiers) did surprisingly well. The offensive tore deep into the territory of their adversary. Only after several weeks, when it became clear that UNITA was unable to repel the attack, did South African forces mobilize to assist them. The Cubans were stopped on the outskirts of the city of Cuito Cuanavale.

Starting in October 1987, a regular battle took place outside Cuito Cuanavale. It was the second largest battle ever fought in Africa – the first was the Battle of El Alamein in 1942.

At the turn of 1987-1988 something quite extraordinary happened. The leaders of South Africa publicly admitted for the first time that their forces were fighting on Angolan territory (which, after all, had officially been an independent country since 1975). This declaration triggered a huge wave of discontent in South Africa itself (people really did not know that South African troops were in Angola; officially they said the army was fighting with paramilitaries in Namibia) and a reaction from the Security Council. The UN called for South Africa to immediately leave the other countries territory. The call was left unanswered.

Concurrently, frantic meetings were taking place in Havana. The situation at Cuito Cuanavale was difficult. There was concern that losing the battle would mean the continuation of the South African offensive deep into Angola. Fidel Castro sent appeals to Moscow for greater military support, but the Kremlin turned a deaf ear towards Havana’s appeals – various phone calls and messages from across the ocean were simply ignored.

Castro then made one of the craziest decisions of his life. He decided to send literally everything that he had to Angola. Thousands of soldiers, planes, armaments, ammunition and medical supplies set off for Africa. Hardly any soldier remained in Cuba, the island was totally defenseless. Castro did this – though it may seem incredible – for ideological reasons. He really, sincerely believed that the communist revolution would triumph in Africa, and that the racist South African regime would be defeated thanks to his soldiers.

At the end of November, new forces reached Cuito Cuanavale. Cuban generals sent to the front removed Soviet commanders from all decision-making. Havana took the lead. Moscow was in shock.

Will Francis choose to make such an act of support for a Ukraine attacked by Russia?

see more

The Battle of Cuito Cuanavale did not end until March 1988. The South African forces and their UNITA allies were forced out.

Pretoria was sure that – as had happened earlier – the Cubans would start withdrawing to their earlier positions. Castro, however, gave a clear signal that his forces were to advance and expel all South African forces from Angola. Neither Moscow nor Washington had expected this. The Cuban troops, meanwhile, were headed south, ultimately stopping just 6 kilometers from the border with Namibia.

The situation became very tense. South Africa made it known to the Cubans that if they entered their territory (which they considered Namibia to be), they would not even rule out the use of nuclear weapons to stop them. Castro was very sure of himself though. He ignored suggestions from Moscow to soften his course and withdraw his soldiers from the border with South Africa. Stoking the atmosphere even further, the Cubans violated Namibian airspace several times.

The situation was not diffused until peace negotiations (and not the first) at the end of July 1988. After several months of talks, South African politicians agreed in the end to withdraw their forces from Angola. In exchange, Cuba was to agree to a ceasefire. It took Angolan politicians to convince the Cubans to accept these provisions.

From that point onward, the situation on the front stabilized. There were still skirmishes but they were local and between the MPLA and UNITA.

Cuba, Angola, the United States and the Soviet Union, took seats at the negotiating table. The Cubans played the lead role during all of the negotiations; they were the ones who discussed all of the most important issues with the Americans. This fact was not revealed for years and it is shocking, since these countries did not actually maintain any relations with one another. Meanwhile, the Cuban and US delegations sat together at the same table and discussed the future of Southern Africa.

The Soviet Union, consumed with its internal problems, was relegated to the background. Fidel Castro considered Gorbachev to be a traitor to communist ideals. The Cubans did not even share any of their observations with the Soviets.

The Angola episode was Fidel Castro’s great triumph. The South African forces left Angola, UNITA declined in importance, the ally of the Cubans, that is the MPLA communists, stayed in power, and in 1990, Namibia gained independence and the first elections were won by Cuba ally SWAPO.

However, Cuba itself paid a heavy price. The Cuban economy was ruined and Cubans had nothing to eat (to make matters worse, Cuban soldiers brought AIDS home with them). After a quarter of a century, Fidel fulfilled his Angolan dream, which, in the long run, turned out to be a catastrophe for the country.

– Anna Szczepańska

– Translated by Nicholas Siekierski