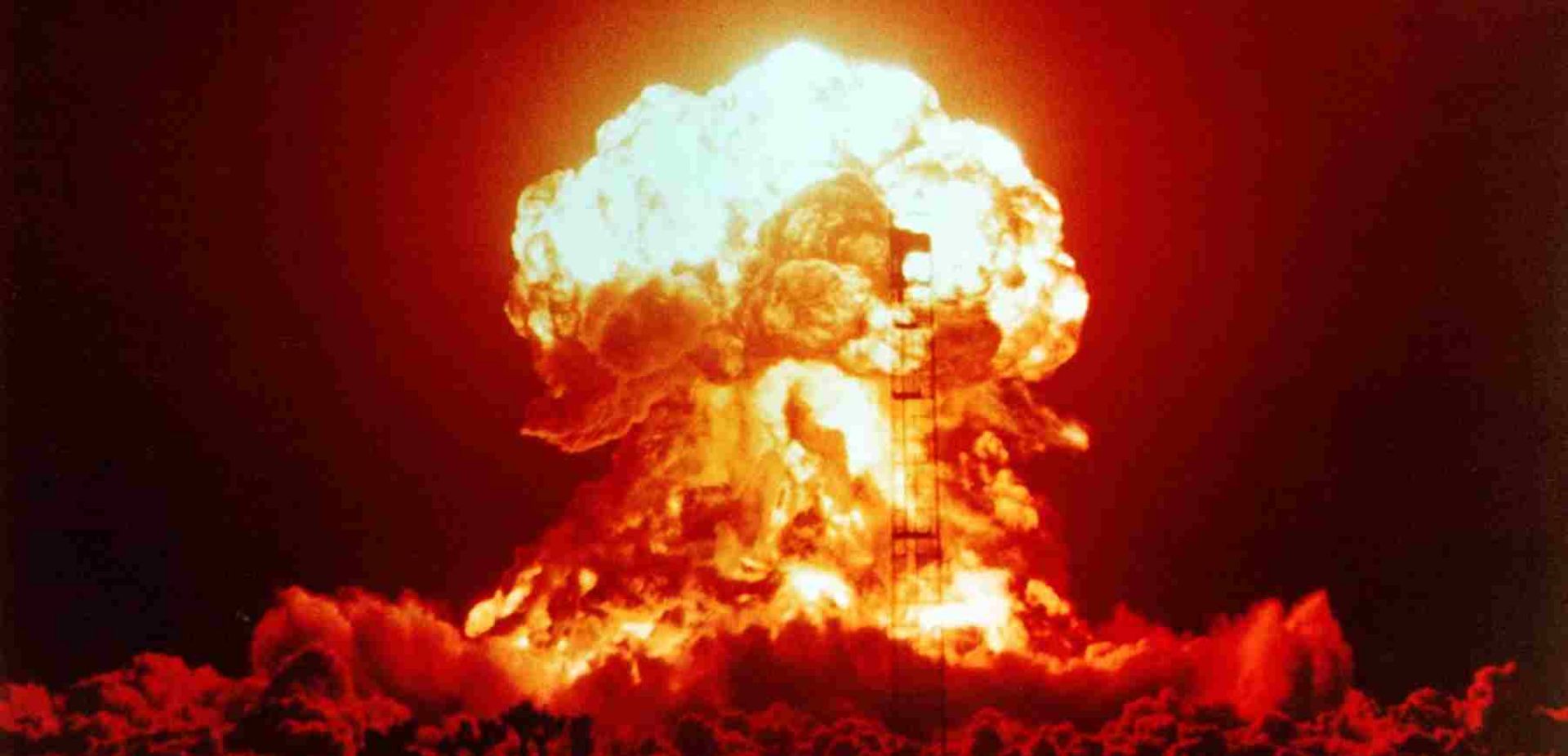

The very attack by the Russian army seemed to us to be something definitive. Many thought that neither the Polish army nor, still less, the Ukrainian one, would last even a few days. Meanwhile, the war goes on and, although cruel, is winnable. Putin wants us to be afraid. To make us think that when he uses nuclear weapons, the world will end.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

So it is better to know it. And we'd better get used to the idea that when we hear the news that the Russians have used it, it won't be the end of the world. The attack by the Russian army also seemed to us to be something definitive. Many thought that neither the Polish army nor, still less, the Ukrainian army would last even a few days. Meanwhile, the opposite is true. The war goes on and, although cruel, is winnable. Putin wants us to be afraid. To make us think that when he uses nuclear weapons, the world will end. It won't.

So it is better to know it. And we'd better get used to the idea that when we hear the news that the Russians have used it, it won't be the end of the world. The attack by the Russian army also seemed to us to be something definitive. Many thought that neither the Polish army nor, still less, the Ukrainian army would last even a few days. Meanwhile, the opposite is true. The war goes on and, although cruel, is winnable. Putin wants us to be afraid. To make us think that when he uses nuclear weapons, the world will end. It won't.

What if the idea of Pan-Mongolism becomes music to Chinese, European and American ears?

see more

Exclusive theories, phantoms that are difficult to assess rationally.

see more

State media claim Poland to prepare an attack on Belarus.

see more

Kremlin factions are conducting a silent war about the taking over power after the death of the president.

see more